Abstract

Dark organic-rich layers (sapropels) have accumulated in Mediterranean sediments since the Miocene due to deep-sea dysoxia and enhanced carbon burial at times of intensified North African run-off during Green Sahara Periods (GSPs). The existence of orbital precession-dominated Saharan aridity/humidity cycles is well known, but lack of long-term, high-resolution records hinders understanding of their relationship with environmental evolution. Here we present continuous, high-resolution geochemical and environmental magnetic records for the Eastern Mediterranean spanning the past 5.2 million years, which reveal that organic burial intensified 3.2 Myr ago. We deduce that fluvial terrigenous sediment inputs during GSPs doubled abruptly at this time, whereas monsoon run-off intensity remained relatively constant. We hypothesize that increased sediment mobilization resulted from an abrupt non-linear North African landscape response associated with a major increase in arid:humid contrasts between GSPs and intervening dry periods. The timing strongly suggests a link to the onset of intensified northern hemisphere glaciation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

‘Green Sahara Periods’ (GSPs) have been a fundamental characteristic of North African climate change for more than 8 Ma ref. 1 Only the most recent GSP during the early-mid Holocene (~11 to 6 thousand years ago, ka; the ‘African Humid Period’) has been studied in detail at numerous locations2,3,4, and it extended to East Africa5,6,7. However, there are few continuous, well-dated GSP records that extend beyond 1.5 Ma (or even beyond the last 300 ka), and no high-resolution North African humidity reconstructions encompass the entire Plio-Pleistocene. Mediterranean sediments contain a particularly rich archive of past GSPs. Here, organic-rich layers (‘sapropels’) form in response to deep-sea anoxia and nutrient inputs when significantly increased run-off enters the basin via the Nile and wider North African margin8. These periods correspond to enhanced boreal summer insolation maxima and minima in Earth’s orbital precession cycle, resulting in a more northerly and intensified African rain belt8,9. Sapropels are a natural testbed for understanding deep-sea redox and carbon burial processes; however, their formation mechanisms are still debated8, and there is currently no continuous high-resolution proxy record of Plio-Pleistocene sapropels.

Ba/Al, Ti/Al and planktic δ18O in Eastern Mediterranean sediments are useful proxies of past GSPs and sapropels. Ba/Al reliably tracks sapropel intervals because it correlates with original organic carbon burial (Corg) in sapropels and is mostly unaffected by post-depositional redox reactions10, while surface water freshening due to monsoon run-off is recorded by strong negative δ18O peaks11,12. Ti/Al in the open Eastern Mediterranean reflects relative variations in North African aeolian vs riverine inputs to the basin13. Aeolian-sourced Ti/Al in the open Eastern Mediterranean is enhanced relative to fluvially-sourced Ti/Al because heavier (Ti-bearing) suspended particles preferentially settle near the Nile fan. Al normalisation (for Ti and Ba) also removes closed-sum effects.

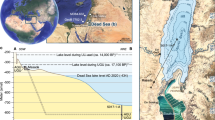

Here, we address the dual need for high-resolution records of North African humidity/aridity changes and sapropel deposition through the entire Plio-Pleistocene, by presenting the first continuous, astronomically dated GSP and sapropel proxy records back to 5.2 Ma from Eastern Mediterranean Ocean Drilling Programme (ODP) Site 967 (Figs. 1–2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). From the same site, we also present high-resolution records of Saharan dust and riverine inputs over the past 5.2 Ma. Our data reveal a fundamental change in sapropel development, provide much-needed climatic context for understanding hominin evolution and migrations out of Africa, and are essential for modelling the mid-Pliocene—the most recent interval with CO2 levels approximating modern levels14.

Eastern Mediterranean sites are from Ocean Drilling Programme (ODP) Leg 160 ref. 29 Base map ©2017 Google Earth, from Image Landsat ©2009 Geobasis-DE/BKG [Data: SIO, NOAA, US Navy, NGA, GEBCO].

Northern and Southern Hemisphere ice-volume changes79 (NH, red; SH, blue) in equivalent sea-level fall (the SH component includes −55 m equivalent sea-level for the modern Antarctic ice sheet), and June 21 insolation at 65°N (yellow) illustrate timing relationships between climate forcing and lithology.

Results and discussion

Green Sahara Periods

Ti/Al, Ba/Al, and planktic δ18O record GSP timings over the Plio-Pleistocene (Fig. 3). The Ba/Al signal is consistent with a typical sapropel sequence10,15, and lower Ti/Al values correspond to Ba/Al spikes, δ18O minima and precession minima. The δ18O record reflects long-term global sea-level/ice volume changes16, with superimposed negative δ18O excursions that relate to African run-off into the Eastern Mediterranean and warming within fresher surface-water layers12,17,18. African run-off reaching ODP967 would have derived primarily from the Nile18,19, which is fed by East African precipitation influenced by both the Indian and African Monsoons and their moisture convergence at the Congo Air Boundary20. African run-off also entered the Eastern Mediterranean from the wider North African margin when the African rain belt migrated northward18,21,22. This rain belt is associated with the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), the West African monsoon, and East African precipitation20,23. Thus, ODP967 δ18O reflects both West and East African precipitation. While changes in local Eastern Mediterranean precipitation over the entire Plio-Pleistocene are not well-constrained, their impacts on ODP967 δ18O are likely to be minimal compared to African run-off because Eastern Mediterranean surface waters are the evaporative source for local precipitation (with little excess δ18O fractionation)8,12. The similar range of δ18O minima at precession minima throughout the record (−1 to −2‰ but reaching −3‰, Fig. 3; note by convention reversed δ18O axis) suggests that maximum African (monsoon) run-off into the Eastern Mediterranean reached roughly similar intensities throughout the Plio-Pleistocene. Furthermore, the ODP967 Ba/Al, Ti/Al and δ18O records all attest to the continuity of run-off maxima and ‘sapropel-like’ Pliocene Corg fluxes.

ODP Site 967 records of planktic foraminifera (G. ruber) δ18O (red), Ti/Al (blue), and Ba/Al (grey) for time intervals 0–1.5 Myr ago (a), 1.5–3 Myr ago (b) and 3–5 Myr ago (c), with time in kiloyears before Present. Upward peaks correspond to precession minima (orange) and inferred Green Sahara Periods (green shading). (See Supplementary Fig. S2 for detail over a selected interval).

The longest continuous (albeit lower-resolution) time-series of Saharan/North African hydroclimate changes extend back to ~4–4.5 Ma and are based on terrigenous (=non-biogenic) sediment fluxes offshore of Northwest Africa and Arabia24,25, where terrigenous components are primarily sourced from aeolian dust25. At ODP967, an isothermal remanent magnetisation (IRM) proxy for haematite (IRM900@120mT; see Methods) reflects Saharan dust inputs to this site26. IRM900@120mT values remain relatively low until ~1.4 Ma, with notable increases at 1.2 and 0.9 Ma, coincident with the Mid-Pleistocene transition (MPT) (Fig. 4e). Increased dust fluxes at the MPT are also observed in a lower resolution ODP967 IRM record extending back to 3 Ma ref. 26,27, and in dust records from ODP sites 664 (Fig. 4h) and 721/722 (Arabian Sea)27. There are also discrepancies among these records, and among terrigenous (dust) records from other ODP sites off Northwest Africa25,27 (Fig. 1). For example, sites more proximal to the Sahara (e.g. ODP659) have high-amplitude dust fluxes throughout the Plio-Pleistocene25, whereas more distal sites (e.g., ODP662/3 and 664) record higher-amplitude dust fluxes from ~3 and 2.7 Ma (Fig. 4g, h). At ODP Site 959, Ti/Al values suggest increasing aeolian dust inputs from ~3.5 Ma, with potentially a slight increase at 3.2 Ma (Fig. 4i), although this might partly reflect Guinea Current changes28. Lower dust inputs tend to coincide with GSPs, but not consistently (Supplementary Fig. S3); instead, they likely relate to distance from dust source areas and prevailing dust trajectories25,27, i.e. factors other than humidity/aridity changes.

a Tectonic event around Sicily54 in Chron 2An.2n; b–e ODP967 Ba/Al, Ti/Al, 400-kyr moving standard deviation of Ti/Al (black) and magnetic dust proxy (IRM900@120mT) (this study). Change-points in (c) are based on changes in the mean (red) and standard deviation (blue) of the Ti/Al time-series (closed triangles) and Ti/Al residuals (open triangles) after removing low-frequency (140–1200 kyr) variability; f pollen zones from ODP Site 659 ref. 32 (green = more humid; yellow/orange = increasing aridity and humid/arid variability); g, h aeolian dust records from offshore West Africa24, 25, i ODP Site 959 Ti/Al (grey)28 with 11-point running average (red); j tree index based on phytoliths from Baringo Basin core BTB13, with 95% confidence intervals37 (downward bars limited to the y-axis); k DSDP Site 231 leaf wax δD with inferred shift to more aridity at 3.3–3.0 Ma ref. 38, l ODP Site 1165 ice-rafted debris (IRD) fluxes51, m global sea-level reconstruction79 based on benthic δ18O (ref. 69). All records are plotted on their original chronology. Vertical shading denotes the Mid-Pleistocene Transition (MPT; grey) and geochemical shift at ODP967 (yellow).

The Plio-Pleistocene sapropel record

Intriguingly, there are no visibly preserved sapropels in most of the Pliocene portion of ODP967 ref. 29 (Fig. 2)—visible sapropels appear from 3.2 Ma onward. However, not all Eastern Mediterranean ODP sites record the same lithological change at 3.2 Ma (Table 1): Sites 964 and 967 lack visible sapropels before this time, while Sites 966 and 969 contain a visible sapropel sequence down to the core base at 4.5 and 5.3 Ma, respectively29. Western Mediterranean sapropels are mostly limited to the last 1.8 Ma and are, therefore, not considered here (Supplementary Table S1). The difference among Eastern Mediterranean sites remains unexplained. It is unlikely to relate to Pliocene sedimentation rates, which are similar among the four sites (Supplementary Fig. S4), but may relate to water depth because Pliocene sapropels are absent from the deepest sites29. Spatial offsets in the timing, duration, and intensity of sapropel formation are expected8,30, but such a dramatic contrast in Pliocene sapropel preservation among Eastern Mediterranean sites implies basin-wide changes in the balance of deep-water oxygen supply (ventilation) vs demand (Corg remineralization and, likely, export).

The ODP967 sapropel-sequence change coincides with a shift to larger amplitude Ba/Al and Ti/Al fluctuations (Fig. 4b–d), a two-to-threefold increase in terrigenous element concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S5), and a shift in the mean and variance of Ti/Al-based on change-point analysis (Fig. 4c). Change-points at ca 4.4 Ma and ca 1.9–1.2 Ma are fewer/more time-diffuse and do not coincide with major lithological (sapropel) changes, hence we do not focus on these changes. At ODP967, element fluxes reflect sediment density changes associated with sapropel lithology (Supplementary Fig. S7); hence, relative variations in terrigenous vs biogenic element concentrations more accurately indicate terrigenous inputs. Run-off and terrigenous sediment inputs to the Levantine Basin are dominantly sourced from North Africa19,22,31, and elevated terrigenous element concentrations at ODP967 tend to be associated with insolation maxima, although not consistently (Supplementary Fig. S6). Plio-Pleistocene Northern Mediterranean sediment sources to ODP967 are unconstrained and, hence, cannot be excluded, but are likely less significant than African sources19,22. The 3.2 Ma geochemical shift and sapropel deposition/preservation change, thus, implies a major increase in monsoon run-off and/or suspended load, or a fundamental reorganisation of Eastern Mediterranean deep-water circulation and sedimentation. We formulate four testable hypotheses (Table 2) that invoke: (a) a marked change in North African climate/landscape (Hypotheses 1–2; H1,2); and (b) Sicily Sill uplift (H3,4). We now consider our results in the context of these scenarios.

African climate/environment shift at 3.2 Ma

Considering H1 (see Table 2), a marked freshwater run-off increase into the Eastern Mediterranean would be registered in ODP967 δ18O, irrespective of the freshwater source. However, ODP967 δ18O reaches similar minima throughout the last 4.5 Ma (Fig. 3). H1 also implies a shift to more rainfall after 3.2 Ma, which is inconsistent with pollen data32 (Fig. 4f) and modelling results33,34,35 that indicate a generally greener Pliocene Sahara (i.e. forests and wetlands). Leaf wax δ13C31 at ODP Site 659 (Fig. 1) is generally more negative in the Pliocene compared with the last glacial cycle, which is consistent with elevated Pliocene North African humidity36. Similarly, high-resolution pollen and tree index records from the Baringo Basin reveal a marked shift to drier conditions at 3.2 Ma ref. 37 (Fig. 4j), which is consistent with leaf wax isotope data from DSDP Site 231 in the Gulf of Aden38 (Fig. 4k). Leaf wax isotope records (δD, δ13C) in that study were interpreted in combination with other regional palaeoclimate records and suggest two main shifts to drier conditions: at 5–4.5 and 3.3–3.0 Ma. Hence, available evidence causes us to reject H1.

H2 implies a more erodible North African landscape from ~3.2 Ma onward, which in turn suggests more arid or variable climate conditions, or the emergence of new—possibly seasonal—drainage pathways. Equally, a reduction in soil-stabilising vegetation would facilitate sediment erosion through existing channels. Pollen records support a shift to increased aridity and climate variability after 3.2 Ma (see above), while dust records are more equivocal: only two ODP sites (662/3 and 664) record a shift to higher amplitude dust inputs at around 3 Ma (Fig. 4g, h). However, aeolian dust records can reflect other factors (e.g. wind patterns, distance to dust source), which could explain some offsets (Sites 662/3 and 664 are more distal from the Sahara than Site 659). Furthermore, if the amplitude increase in ODP967 Ti/Al variations (aeolian vs riverine proxy) at 3.2 Ma is African-climate driven, then the lack of a coeval shift in ODP967 IRM900@120mT (aeolian proxy) implies that the Ti/Al change primarily reflects a change in riverine rather than aeolian components. At ODP967, this component is sourced primarily from the Nile18,19. While the Sahara has likely existed since the Miocene39, the Nile evolved through the Plio-Pleistocene40,41,42. The timings of its various development stages are not well-constrained, but a recent synthesis41 proposes a Late Pliocene/early Pleistocene connection of the Blue Nile/Atbara-Tekeze rivers to the palaeo-Nile, and the emergence of the modern Egyptian Nile flood plain and delta (the White Nile joined the main channel within the last 0.5 Ma ref. 41). Nile evolution could, therefore, account for a major mid/late Pliocene shift in drainage pathways and suspended sediment.

It is implicit to H2 (and inferred from our ODP967 δ18O record) that freshwater run-off fluxes during GSPs must have been decoupled from long-term changes in suspended sediment loads. Several lines of evidence suggest that this is plausible. First, factors determining river sediment loads over geological time reflect a complex interplay of tectonics (e.g. rock type, relief) and climate (e.g. precipitation, run-off). Peak suspended load does not always correspond to peak run-off, unlike typical annual cycles, so landscape changes driven by tectonic (and climate) evolution can result in more erodible surfaces, and thus increased sediment loads, without an attendant change in local rainfall43. Second, ecological modelling and data suggest that African biomes are highly sensitive to small reductions in precipitation44. Major biome changes in tropical Africa have been simulated without a total annual precipitation change, simply by altering rainfall seasonality45. Moreover, the inclusion of soil feedbacks in GSP simulations can reproduce pollen-inferred vegetation shifts at around 400 mm/yr mean precipitation, relative to ~600 mm/yr in the absence of soil feedbacks46.

We also cannot ignore the potential effects of large-scale global changes on African climate/ landscape at ca 3.2 Ma. The first major Northern Hemisphere glaciation (based on global benthic δ18O) is in stages M2–MG2 at 3.295–3.340 Ma ref. 47 (Figs. 2 and 4n), although the onset was spatially variable and as early as 3.6 Ma ref. 48. However, the average time-dependent standard deviation of benthic δ18O from 25 high-resolution records starts to increase at 3.2 Ma ref. 48. Stronger high-latitude cooling and intra- and inter-hemispheric SST gradients are observed from ~3.3 Ma ref. 49,50, coeval with a tenfold IRD (ice-rafted debris) flux increase off East Antarctica51 (Fig. 4m). Central Asian aridification has also been dated to 3.3 Ma, based on halite content, grain size, and magnetic proxies from the Qaidam Basin52. All of these developments would have impacted atmospheric dynamics and latitudinal temperature gradients that drive seasonal North African climate variability, so they could relate to either H1 or H2. We have rejected H1. Therefore, based on available evidence, we retain H2 as a possibility.

Strait of Sicily reconfiguration

Considering H3 and H4 (Table 2), Mediterranean tectonics could alter basin and sill depths, which would in turn affect deep-water ventilation. Tectonics within the wider Eastern Mediterranean catchment could also affect terrigenous fluxes to the seafloor, by rerouting transportation pathways and/or increasing continental erosion. The Mediterranean Basin has been tectonically active since reaching its modern configuration in the Oligocene-Miocene53. Detailed palaeomagnetic work in Sicily suggests a rapid (80,000–100,000 yr) differential clockwise rotation at 3.21 Ma, near the C2An.2n-C2An.2r boundary54 (Fig. 4a). The rotation compressed the Sicilian fold-and-thrust belt and its foreland54,55,56 and accelerated the Tyrrhenian Sea opening between 3.5 and 2 Ma ref. 54, and is consistent with the evidence of middle Pliocene tectonics in the Sicilian Strait56. The timing corresponds with the Trubi-Narbone Formation boundary and may correspond to a rotational phase in northern Italy and a tectonic event north of Crete54.

The close timing between lithological changes at ODP967 (and likely also at Site 964 ref. 29) and inferred tectonic adjustment of the Sicilian Strait is tantalising. In the modern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean deep-water flushing over the Sicily sill depends on Bernoulli aspiration (akin to ‘pulling’ waters out of the eastern basin) and Eastern Mediterranean deep-water formation ‘pushing’ deep waters out8. At the present sill depth (440 m), Bernoulli aspiration is limited to <800 m; deep Eastern Mediterranean ventilation, therefore, relies on the deep-water formation pump. During sapropel phases, this pump was effectively turned off, leading to anoxic deep waters8. Calculations suggest that a 200–400 m deeper Sicily Sill would only marginally affect deep Eastern Mediterranean ventilation (Methods); nevertheless, we retain H3 and H4 for further evaluation.

Deep-sea ventilation versus carbon export

Reduced deep Eastern Mediterranean ventilation during sapropel/monsoon periods is forced by surface buoyancy gain (i.e. freshening), yet the relationship between sapropel Corg content and degree of buoyancy forcing is complex8. Sapropel Corg is typically of marine origin, but the type, mechanism, and amount of primary/export production is uncertain; however, consensus suggests a well-developed deep chlorophyll maximum for most sapropels8. If increased terrigenous fluxes from 3.2 Ma onward (e.g. hypothesis H2) brought more labile terrestrial Corg and nutrients to the Eastern Mediterranean, they may have fuelled higher primary productivity and Corg export rates relative to the Pliocene, leading to more intensely developed sapropels. Evidence to support/refute this is equivocal or non-existent. Riverine nutrient inputs remain unquantified even for the most recent sapropel57. Pliocene sapropels in astronomically dated sections from Sicily and Cyprus contain lower Corg concentrations than typical Pleistocene sapropels58,59, but sapropels in outcrops typically contain less Corg and total N than sapropels in offshore cores60. There is general consensus among earlier studies60,61,62 that Pliocene and Pleistocene sapropels are similar, and that Pliocene sapropels can contain high Corg (≤30%) ref. 62, but the down-core depth intervals studied in these examples correspond to ages younger than 3.1 Ma. Meanwhile, similar early/mid-Pliocene and Pleistocene abundances of Florisphaera profunda—indicative of a deep chlorophyll maximum—are observed in sapropels from outcrops in Cyprus59 and at ODP967 ref. 63, implying similarly elevated Pliocene and Pleistocene primary productivity during sapropel deposition.

Nonetheless, hypothesis H2 cannot account for Eastern Mediterranean ventilation changes after 3.2 Ma, so improved sapropel preservation after 3.2 Ma must be solely due to increased Corg export. In contrast, Sicilian Strait shoaling (H3-4) could, in principle, induce an increased tendency toward Eastern Mediterranean deep-water stagnation, but—as yet—evidence remains circumstantial and sparse. Major benthic foraminiferal turnovers are documented between 3.6 and 2.6 Ma in the Punta Piccola section64 (Southern Italy) and deep ODP sites in the Western and Eastern Mediterranean basins65, which indicate increasing instability in bottom-water conditions. However, the main change is focussed at ~2.7 Ma, some 500,000 years after the events discussed here. Coupled Mg/Ca-δ18O and εNd trends suggest that Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW) intensified between 3.5 and 3.3 Ma ref. 66, but this pre-dates our observed geochemical shift. Nevertheless, seismic data and core sediments from the Gulf of Cadiz (Fig. 1) indicate a hiatus at ca 3.2–3.0 Ma and subsequent contourite deposition, which is attributed to MOW intensification in response to Strait of Gibraltar tectonics67. The timing is based on preliminary biostratigraphic results and might be older (~3.4–3.3 Ma) according to a revised mid-late Pliocene chronology for Site U1387 ref. 68. Regardless, deep-water exchange through the Sicilian Strait, rather than the Strait of Gibraltar, is the critical factor for deep ventilation of the Eastern basin8. Contributions to Pliocene buoyancy forcing from local precipitation/evaporation are unknown, but we assume that they were negligible relative to African run-off forcing. Likewise, elevated SSTs cannot solely account for buoyancy forcing, given that they only partially contribute to water-column stratification during the Last Interglacial sapropel formation17,18, and mostly in response to salinity-driven stratification.

Conclusions

We have evaluated different hypotheses (climatic vs tectonic) to explain a marked shift in Eastern Mediterranean sediments 3.2 Ma ago. We find that sill tectonics (H3,4) could account for reduced ventilation after 3.2 Ma (which best explains subsequently increased ODP967 Ba and S concentrations) and may coincide with inferred tectonic activity in the Strait of Gibraltar. However, hypothesis H3 cannot satisfactorily account for a doubling (or more) of terrigenous element concentrations at ODP967 after 3.2 Ma. Hypothesis H4 might account for this if the terrigenous influx was locally sourced (i.e. Eastern Mediterranean borderlands), but circumstantial evidence is lacking, and—more importantly—Pleistocene terrigenous sediments at ODP967 predominantly originated from North Africa19. Conversely, the non-linear response of riverine terrigenous loads to African climate/landscape evolution (hypothesis H2) better accounts for increased ODP967 terrigenous element concentrations and Ti/Al fluxes after 3.2 Ma. H2 can also be directly linked to mid-late Pliocene global climate evolution. The 3.2 Ma shift could represent a critical North African landscape transition in response to a global climate state shift to icehouse conditions69. Increased geochemical signal variance is common prior to critical transitions in Eastern Mediterranean sediments70, and the biggest systematic Ti/Al variance increase is from 3.4 to 3.2 Ma (Fig. 4d). African pollen evidence attests to a more arid Pleistocene compared to the Pliocene32,71, and a significantly more erodible landscape must exist before a stepwise amplitude increase in fluvial suspended sediment can occur. Furthermore, North African desert-soil albedo and vegetation feedbacks strongly amplify rainfall variability46,72,73. The 3.2 Ma increase in ODP967 Ti/Al and fluvial-sourced terrigenous elements might, therefore, signify the onset of modern-day North African aridity. Further quantitative studies (e.g. weathering proxies) are needed to confirm this. Nevertheless, we cannot (yet) fully reject H4. It is conceivable that both H2 and H4 are valid and were coupled to major global climatic and tectonic changes; future model-data comparisons should test this possibility.

Methods

Bulk element geochemistry

We combine published x-ray fluorescence (XRF) core-scanner data from ODP Site 967 spanning 0–3 Ma ref. 15 with new XRF core-scanner data for the 3–5 Ma interval. Scanning was performed on archive core sections at MARUM University of Bremen, on an Avaatech XRF core scanner. Core sections were covered with 4 mm-thick Ultralene film and measured at 50 and 30 kV with 0.55 mA current and with a Cu and Pd-thick filter, respectively, and at 10 kV with 0.035 mA current (no filter); count time for all runs was 7 s. Element ‘counts’ for the entire 0–5 Ma interval were converted into element concentrations by multivariate log-ratio calibration74, using published35,75 and new wavelength dispersive (WD)-XRF reference element concentrations (Supplementary Figs. S8, S9). For these, 42 bulk sediment samples were chosen to cover a range of lithologies based on the XRF scan, then 1 cm3 dried ground sample was mixed with a lithium tetraborate/lithium metaborate flux and fused into 39 mm diameter beads. Major element abundances were analysed by WD-XRF using a Bruker S8 Tiger™ spectrometer at Geoscience Australia. Loss on ignition (LOI) was measured by gravimetry after combustion at 1000 °C. One in every ten samples was duplicated along with multiple analyses of three international standards (NCS DC70306, MAG-1, ML-2) and an internal basalt standard (WG1). Quantification limits for all major element oxides are <0.2% and reproducibility is within 1%.

The upper 40 m (0–1.3 Ma) of ODP967 contains cm-thick turbidites, which are not always visible, and which typically occur within sapropels76. Sudden ‘extreme’ enrichments in Ti, Si, Zr, and to a lesser extent Fe and K, and corresponding Ca depletions, may therefore indicate a turbidite75. Anomalous K spikes (relative to background values) are apparent at 2.3 and 2.9 Ma (Supplementary Fig. S4), but elsewhere any potential turbidite signal is obfuscated by the dominant sapropel/marl signal.

ODP967 chronology

Published age-depth tie-points for the 0–3 Ma interval are based on tuning a principal-component derived sapropel proxy to precession15. Here, we extend the age model to 5 Ma by tuning the Ba/Ti record from XRF core-scanning to precession minima with zero phase lag (Supplementary Fig. S1). Phase lags between a sapropel mid-point and nearest precession minimum/insolation maximum can be up to 3 ky but are not systematic and are likely limited to major deglaciations12, hence (minor) lags would only be expected after the MPT.

Environmental magnetism

ODP967 U-channel samples were sliced at 1-cm intervals into non-magnetic plastic cubes and measured on a 2-G Enterprises cryogenic magnetometer at the Australian National University (ANU). IRM900@120mT was obtained after imparting a 900 mT induction in a direct current field, followed by alternating field (AF) demagnetisation in a peak 120 mT field.

Stable oxygen isotopes (δ18O)

Bulk sediment samples were washed through 63 μm sieves with DI water and the residue was oven-dried at 45 °C for 24 h. Globigerinoides ruber (white) specimens were picked from the >300 μm size fraction, adhering to ‘sensu stricto’ morphotypes and size range (±25 μm). Picked tests (typically 10–20, depending on abundance) were gently crushed and cleaned by briefly ultrasonicating in methanol, then air-dried after decanting the fine suspended matter. Samples were analysed at ANU using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Delta Advantage mass spectrometer coupled to a Kiel IV carbonate device for sample digestion. Isotope data were normalised to the Vienna Peedee Belemnite (VPDB) scale using NBS-19 or IAEA-603, and NBS-18. External reproducibility (1σ) was always better than 0.08‰.

Bernoulli aspiration depth (d)

We use values from ref. 8 in the equation of ref. 77.

where h1 approximates the depth of the open Eastern Mediterranean (~2000 m), h2 is the Sicily Sill depth, u is the mean outflow velocity in the Sicilian Strait (0.2 m s−1), Δρy is the vertical density gradient below the sill depth (0.03 kg m−3 today), ρo is the density of the outflow layer at the sill (~1027 kg m−3), and g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m s−1). For a 200 and 400 m deeper sill (h2 = 600 and 800 m), d is −900 and −1000 m, respectively. Allowing a reduced density gradient below sill depth (Δρy = 0.02 kg m−3, based on the modern Strait of Gibraltar), d is then −1010 and −1160 m, respectively. Thus, Eastern Mediterranean deep waters below ~1000 m would be poorly ventilated even if the Sicily Sill was 400 m deeper.

Data analysis

Change-points were estimated using the MATLAB built-in function ‘findchangepts’, following ref. 78. Change-points were determined based on the mean and standard deviation of the raw geochemical records, and a maximum of n = 3 change-points was stipulated as a parsimonious balance between constraining output to the most significant changes while allowing a >1 outcome. The moving standard deviation of the ODP967 Ti/Al record was calculated using the MATLAB built-in function ‘movstd’.

Data availability

ODP Site 967 data from this study are available from Panagea (www.pangaea.de) under ‘Plio-Pleistocene scanning XRF, stable isotope and environmental magnetic data from ODP Site 967’ and are also available as online Supplementary Data accompanying this article.

Change history

09 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00357-1

References

Larrasoaña, J. C., Roberts, A. P., Rohling, E. J. Dynamics of green Sahara periods and their role in hominin evolution. PLoS ONE 8, e76514 (2013).

Ritchie, J. C., Eyles, C. H. & Haynes, C. V. Sediment and pollen evidence for an early to mid-Holocene humid period in the eastern Sahara. Nature 314, 352–355 (1985).

Drake, N. A., Blench, R. M., Armitage, S. J., Bristow, C. S. & White, K. H. Ancient water courses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 458e462 (2010).

Shanahan, T. M. et al. The time-transgressive termination of the African humid period. Nat. Geosci. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2329 (2015).

Street, F. A. & Grove, A. T. Environmental and climatic implications of late quaternary lake-level fluctuations in Africa. Nature 261, 385–390 (1976).

Gasse, F. Hydrological changes in the African tropics since the last glacial maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 189–211 (2000).

Tierney, J. E., Lewis, S. C., Cook, B. I., LeGrande, A. N. & Schmidt, G. A. Model, proxy and isotopic perspectives on the East African humid period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 103–112 (2011).

Rohling, E. J., Marino, G. & Grant, K. Mediterranean climate and oceanography, and the periodic development of anoxic events (sapropels). Earth-Sci. Rev. 143, 62–97 (2015).

Rossignol-Strick, M. Mediterranean quaternary sapropels, an immediate response of the African monsoon to variation of insolation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 49, 237–263 (1985).

Thomson, J., Mercone, D., de Lange, G. J. & van Santvoort, P. J. M. Review of recent advances in the interpretation of eastern Mediterranean sapropel S1 from geochemical evidence. Mar. Geol. 153, 77–89 (1999).

Emeis, K. C. et al. Eastern Mediterranean surface water temperatures and δ18O composition during deposition of sapropels in the late Quaternary. Paleoceanography 18 https://doi.org/10.1029/2000PA000617 (2003).

Grant, K. M., Grimm, R., Mikolajewicz, U., Ziegler, M. & Rohling, E. J. The timing of Mediterranean sapropel deposition relative to insolation, sea-level and African monsoon changes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 140, 125–141 (2016).

Lourens, L. J., Wehausen, R. & Brumsack, H. J. Geological constraints on tidal dissipation and dynamical ellipticity of the Earth over the past three million years. Nature 409, 1029–1033 (2001).

Martinez-Boti, M. A. et al. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature 518, 49–53 (2015).

Grant, K. M. et al. A 3 million year index for North African humidity/aridity and the implication of potential pan-African Humid periods. Quat. Sci. Rev. 171, 100–118 (2017).

Rohling, E. J. et al. Sea-level and deep-sea-temperature variability over the past 5.3 million years. Nature 508, 477–482 (2014).

Rodriguez-Sanz, L. et al. Penultimate deglacial warming across the Mediterranean Sea revealed by clumped isotopes in foraminifera. Sci. Rep. 7, 16572 (2017).

Amies, J. D., Rohling, E. J., Grant, K. M., Rodriguez-Sanz, L. & Marino, G. Quantification of African monsoon runoff during last interglacial sapropel S5. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 1487–1516 (2019).

Wu, J., Filippidi, A., Davies, G. R. & de Lange, G. J. Riverine supply to the eastern Mediterranean during last interglacial sapropel S5 formation: a basin-wide perspective. Chem. Geol. 485, 74–89 (2018).

Nicholson, S. E. A review of climate dynamics and climate variability. In Eastern Africa in The Limnology, Climatology and Paleoclimatology of the East African Lakes (eds Johnson, T. C., Odada, E. O. & Whittaker, K. T.) 25–56 (Gordon and Breach, 1996).

Rohling, E. J. et al. African monsoon variability during the previous interglacial maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 202, 61–75 (2002).

Osborne, A. H. et al. A humid corridor across the Sahara for the migration “Out of Africa” of early modern humans 120,000 years ago. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16,444–16,447 (2008).

Singarayer, J. S. & Burrough, S. L. Interhemispheric dynamics of the African rainbelt during the late Quaternary. Quat. Sci. Rev. 124, 48–67 (2015).

Ruddiman, T. F. & Janecek, T. R. Plio-Pleistocene biogenic and terrigenous fluxes at equatorial Atlantic sites 662, 663, and 664. Proc. ODP Sci. Res. 108, 211–240 (1989).

deMenocal, P. B. Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Science 270, 53–59 (1995).

Larrasoaña, J. C., Roberts, A. P., Rohling, E. J., Winklhofer, M. & Wehausen, R. Three million years of monsoon variability over the northern Sahara. Clim. Dyn. 21, 689–698 (2003).

Trauth, M. H., Larrasoaña, J. C. & Mudelsee, M. Trends, rhythms and events in Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 399–411 (2009).

Vallé, F., Westerhold, T. & Dupont, L. M. Orbital‑driven environmental changes recorded at ODP Site 959 (eastern equatorial Atlantic) from the Late Miocene to the Early Pleistocene. Int. J. Earth Sci. 106, 1161–1174 (2017).

Emeis, K. C., Sakamoto, T., Wehausen, R. & Brumsack, H. J. The sapropel record of the eastern Mediterranean Sea — results of Ocean Drilling Program Leg 160. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 158, 371–395 (2000).

Casford, J. S. L. et al. A dynamic concept for eastern Mediterranean circulation and oxygenation during sapropel formation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 190, 103–119 (2003).

Williams, M. A. J. et al. Causal links between Nile floods and eastern Mediterranean sapropel formation during the past 125 kyr confirmed by OSL and radiocarbon dating of Blue and White Nile sediments. Quat. Sci. Rev. 130, 89–108 (2015).

Leroy, S. & Dupont, L. Development of vegetation and continental aridity in northwestern Africa during the Late Pliocene: the pollen record of ODP Site 658. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 109, 295–316 (1994).

Salzmann, U., Haywood, A. M., Lunt, D. J., Valdes, P. J. & Hill, D. J. A new global biome reconstruction and data-model comparison for the Middle Pliocene. Global Ecol. Biogeogr 17, 432–447 (2008).

Colleoni, F., Cherchi, A., Masina, S. & Brierley, C. M. Impact of global SST gradients on the Mediterranean runoff changes across the Plio-Pleistocene transition. Paleoceanography 30, 751–767 (2015).

de Boer, M., Peters, M. & Lourens, L. J. The transient impact of the African monsoon on Plio-Pleistocene Mediterranean sediments. Clim. Past 17, 331–344 (2021).

Kuechler, R. R., Dupont, L. M. & Schefus, E. Hybrid insolation forcing of Pliocene monsoon dynamics in West Africa. Clim. Past 14, 73–84 (2018).

Yost, C. L. et al. Phytoliths, pollen, and microcharcoal from the Baringo Basin, Kenya reveal savanna dynamics during the Plio-Pleistocene transition. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 570, 109779 (2020).

Liddy, H. M., Feakins, S. J. & Tierney, J. E. Cooling and drying in northeast Africa across the Pliocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 430–438 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Aridification of the Sahara desert caused by Tethys Sea shrinkage during the late Miocene. Nature 513, 401–404 (2014).

Said, R. The Geological Evolution of the River Nile (Springer, 1981).

Abdelsalam, M. G. The Nile’s journey through space and time: a geological perspective. Earth Sci. Rev. 177, 742–773 (2018).

Sagy, Y., Dror, O., Gardosh, M. & Reshef, M. The origin of the Pliocene to recent succession in the Levant basin and its depositional pattern, new insight on source to sink system. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 120, 104540 (2020).

Williams, M. River sediments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 370, 2093–2122 (2012).

Hely, C. et al. Sensitivity of African biomes to changes in the precipitation regime. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr 15, 258–270 (2006).

Gritti, E. S. et al. Simulated effects of a seasonal precipitation change on the vegetation in tropical Africa. Clim. Past 6, 169–178 (2010).

Chen, W. et al. Feedbacks of soil properties on vegetation during the Green Sahara period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 240, 106389 (2020).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, PA1003 (2005).

Mudelsee, M. & Raymo, M. E. Slow dynamics of the Northern Hemisphere glaciation. Paleoceanography 20, PA4022 (2005).

Lawrence, K., Sosdian, S., White, H. & Rosenthal, Y. North Atlantic climate evolution through the Plio-Pleistocene climate transitions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 300, 329–342 (2010).

Herbert, T. D. et al. Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 9, 843–847 (2016).

Passchier, S. Linkages between East Antarctic ice sheet extent and Southern Ocean temperatures based on a Pliocene high‐resolution record of ice‐rafted debris off Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Paleoceanography 26, PA4204 (2011).

Su, Q. et al. Central Asian drying at 3.3 Ma linked to tropical forcing? Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10,561–10,567 (2019).

van Hinsbergen, D. J. J. et al. Orogenic architecture of the Mediterranean region and kinematic reconstruction of its tectonic evolution since the Triassic. Gondwana Res. 81, 79–229 (2020).

Duermeijer, C. E. & Langereis, C. G. Astronomical dating of a tectonic rotation on Sicily and consequences for the timing and extent of a middle Pliocene deformation phase. Tectonophysics 298, 243–258 (1998).

Oldow, J. S., Channell, J. E. T., Catalano, R. & D’Argenio, B. Contemporaneous thrusting and large-scale rotations in the western Sicilian fold and thrust belt. Tectonics 9, 661–681 (1990).

Catalano, R., Di Stefano, P., Sulli, A. & Vitale, F. P. Paleogeography and structure of the central Mediterranean: Sicily and its offshore area. Tectonophysics 260, 291–323 (1996).

Grimm, R. et al. Late glacial initiation of Holocene eastern Mediterranean sapropel formation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7099 (2015).

Planq, J. et al. Multi-proxy constraints on sapropel formation during the late Pliocene of central Mediterranean (southwest Sicily). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 420, 30–44 (2015).

Athanasiou, M. et al. Sea surface temperatures and environmental conditions during the “warm Pliocene” interval (~4.1–3.2 Ma) in the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus). Glob. Planet. Change 150, 46–57 (2017).

Nijenhuis, I. A., Becker, J. & De Lange, G. J. Geochemistry of coeval marine sediments in Mediterranean ODP cores and a land section: implications for sapropel formation models. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 165, 97–112 (2001).

Passier, H. F. et al. Sulphidic Mediterranean surface waters during Pliocene sapropel formation. Nature 397, 146–149 (1999).

Nijenhuis, I. A. & De Lange, G. J. 2000. Geochemical constraints on Pliocene sapropel formation in the eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Geol. 163, 41–63 (2000).

Castradori, D. Calcareous nannofossils in the basal Zanclean of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea: remarks on paleoceanography and sapropel formation. Proc. ODP Sci. Res. 160, 113–124 (1998).

Sgarrella, F., Di Donato, V. & Sprovieri, R. Benthic foraminiferal assemblage turnover during intensification of the Northern Hemisphere glaciation in the Piacenzian Punta Piccola section (Southern Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 333-334, 59–74 (2012).

Haywood, B. W., Sabaa, A. T., Kawagata, S. & Grenfell, H. R. The Early Pliocene re-colonisation of the deep Mediterranean Sea by benthic foraminifera and their pulsed Late Pliocene–Middle Pleistocene decline. Mar. Micropaleontol. 71, 97–112 (2009).

Khélifi, N. et al. A major and long-term Pliocene intensification of the Mediterranean outflow, 3.5–3.3 Ma ago. Geology 37, 811–814 (2009).

Hernandez-Molina, F. J. et al. Onset of Mediterranean outflow into the North Atlantic. Science 344, 6189 (2014).

Tzanova, A. & Herbert, T. D. Regional and global significance of Pliocene sea surface temperatures from the Gulf of Cadiz (Site U1387) and the Mediterranean. Glob. Planet. Change 133, 371–377 (2015).

Westerhold, T. et al. An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science 369, 1383–1387 (2020).

Hennekam, R. et al. Early-warning signals for marine anoxic events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089183 (2020).

Lupien, R. L. et al. Vegetation change in the Baringo Basin, East Africa across the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation 3.3–2.6 Ma. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 570, 109426 (2019).

Knorr, W. & Schnitzler, K.-G. Enhanced albedo feedback in North Africa from possible combined vegetation and soil-formation processes. Clim. Dyn. 26, 55–63 (2006).

Tierney, J. E., Pausata, F. S. R. & deMenocal, P. B. Rainfall regimes of the Green Sahara. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601503 (2017).

Weltje, G. J. et al. in Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores (eds Croudace, I. W. & Rothwell, R. G.) Ch. 21 (Springer, 2015).

Konijnendijk, T., Ziegler, M. & Lourens, L. Chronological constraints on Pleistocene sapropel depositions from high-resolution geochemical records of ODP sites 967 and 968. Newsl. Stratigr. 47, 263–282 (2014).

Emeis, K.-C. et al. Proc. ODP Initial Reports (160: College Station, TX (Ocean Drilling Program), 1996).

Seim, H. & Gregg, M. C. The importance of aspiration and channel curvature in producing strong vertical mixing over a sill. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 3451–3472 (1997).

Killick, R., Fearnhead, P. & Eckley, I. A. Optimal detection of changepoints with a linear computational cost. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 107, 1590–1598 (2012).

Rohling, E. J. et al. Sea level and deep-sea temperature reconstructions suggest quasi-stable states and critical transitions over the past 40 million years. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf5326 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Australian Research Council grants DE190100042 (K.M.G.), DP190100874 (A.P.R. and D.H.), DP2000101157, and FL1201000050 (E.J.R.), Australia‐New Zealand IODP Consortium (ANZIC) Legacy/Special Analytical Funding grant LE160100067 (K.M.G. and L.R.-S.), the Netherlands Earth System Science Centre (NESSC) gravitation grant 024.002.001 (L.J.L.), and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) through NWO-ALW grant 865.10.001 (L.J.L.). We thank P. deMenocal for supplying ODP Site 664 data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.G. designed and led the study and write-up; K.M.G., U.A., J.D.A., T.P., Y.Q. and L.R.-S. generated δ18O and magnetism data; D.H., P.H. and X.Z. assisted with magnetism measurements; D.L. performed XRF core-scanning; D.L. and T.W. developed the ODP967 composite depth splice and chronology; K.M.G. and R.H. calibrated scanning XRF data; K.M.G. and S.G. performed WD-XRF analyses; L.J.L. contributed WD-XRF data; E.J.R., A.P.R. and all the above co-authors contributed to manuscript development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Clare Davis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grant, K.M., Amarathunga, U., Amies, J.D. et al. Organic carbon burial in Mediterranean sapropels intensified during Green Sahara Periods since 3.2 Myr ago. Commun Earth Environ 3, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00339-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00339-9

This article is cited by

-

Low-frequency orbital variations controlled climatic and environmental cycles, amplitudes, and trends in northeast Africa during the Plio-Pleistocene

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Hydroclimate variability in the central Mediterranean during MIS 17 interglacial (Middle Pleistocene) highlights timing offset with monsoon activity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Sill-controlled salinity contrasts followed post-Messinian flooding of the Mediterranean

Nature Geoscience (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.