Key Points

-

Warns the reader that late presentation of maxillary sinus tumours is common due to the nonspecific nature of presenting symptoms.

-

Stresses how performing a simple cranial nerve examination or diagnostic imaging can be key to a definitive diagnosis.

-

Underlines how prompt communication between specialities and care providers is essential when presenting symptoms of facial pain are of an atypical nature.

Abstract

Objective Malignant tumours of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are rare and late presentation of a maxillary sinus tumour is common due to the vague nature of the symptoms which can delay diagnosis.

Methods We report a female with a maxillary sinus tumour who was initially diagnosed with chronic idiopathic facial pain (CIFP) and sinusitis, which subsequently led to a delay in diagnosis and treatment of her tumour.

Results There was no clinical extra- or intra-oral pathology, however, she had varying clinical presentations of facial pain, anosmia, loss of gustatory function, and infra-orbital nerve paraesthesia. CT and MRI scans confirmed obliteration of the left maxillary sinus by a solid mass involving ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses and some cranial nerves. Biopsy confirmed a poorly differentiated carcinoma of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses and invasion of the cavernous sinus.

Conclusion A morbid, but hidden tumour was left undiagnosed due to the unusual presentation of the patient's symptoms. It is essential that all patients are managed holistically and thorough historical, clinical and radiographic examination and appropriate investigations are carried out to prevent unnecessary and potentially time-wasting treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malignant tumours of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses comprise less than 1% of all malignancies, with poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus being the most common.1

Late presentation of maxillary sinus tumours is common due to the nonspecific nature of the symptoms which can delay diagnosis. This can result in more advanced primary site disease in maxillary sinus tumours. Many of the presenting symptoms, such as nasal obstruction, nasal discharge and cheek pain, may be ascribed to other diagnoses such as chronic idiopathic facial pain (CIFP), acute sinusitis or allergic rhinitis.2

We present a patient with a maxillary sinus tumour who was initially diagnosed with CIFP and sinusitis before referral to a specialist centre, which led to a delay in diagnosis and treatment of her malignant disease.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old woman, diagnosed with epidermolysis bullosa (EB Weber-Cockayne: keratin 14), was referred by her consultant dermatologist in September 2010 to the national adult EB oral care service at the Periodontal Unit, Birmingham Dental Hospital, regarding recalcitrant chronic pain affecting her left maxilla and a sore mouth.

She presented with a history of pain commencing in February 2010, with soreness over her palate and an absence of visible signs of pathology when seen by her general dental practitioner. In July 2010 she developed a tingling sensation over the left side of her nose and was prescribed antibiotics by her medical practitioner under a presumptive diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis.

Subsequently, she developed what was diagnosed as, significant chronic neuropathic pain in her left maxilla, radiating to her eye and nose with no triggering, exacerbating or relieving factors. Her general medical practitioner diagnosed potential trigeminal neuralgia and prescribed carbamezapine. The patient's symptoms intensified and she was prescribed strong analgesics which improved but did not resolve her symptoms completely, demonstrating a likely organic rather than supratentorial nature to her pain. The analgesics were therefore discontinued and her general medical practitioner arranged for urgent CT and MRI scans of the head to be performed and delivered to the dental hospital in time for the consultation.

On presentation at the periodontal department of the dental hospital in September 2010, she reported numbness around the left maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve. She described varying clinical presentations of facial pain, anosmia, loss of gustatory function and paraesthesia which mapped across the maxillary division of the left trigeminal nerve, but did not involve the ophthalmic or mandibular divisions. There were no visible extra- or intra-oral signs of pathology.

When questioned she described no history of ulceration or vesicles, but had suffered from a herpes zoster infection (shingles) in April 2010, although involving a right thoracic dermatome.

She presented her blood investigations which demonstrated that her inflammatory markers were raised: C-reactive protein was raised at 6 mg/L, and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 21 mm/h. Her alanine transaminase (ALT) was also raised to 61 u/L, consistent with an existing medical history of primary biliary cirrhosis. Other routine laboratory findings were normal.

There was no visible head or neck pathology and no cervical lymphadenopathy. A cranial nerve examination was performed, which revealed signs and symptoms related to her Ist cranial nerve (olfactory), her Vth cranial nerve (trigeminal) and also her IXth (hypoglossal) and potentially the chorda tympani branch of the VIIth cranial nerve (facial), and raising suspicion of a space occupying lesion of the left maxillary antrum and/or base of skull.

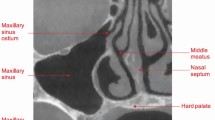

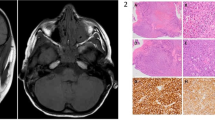

The patient had bought her MRI and CT scans to her consultation at the dental hospital which had yet to be officially reported on (Figs 1, 2 and 3). It was therefore unnecessary to take further radiographic views at this consultation. The scans revealed obliteration of the left maxillary sinus by a solid mass, erasure of lateral walls and ethmoid sinuses and sphenoid sinus involvement.

Expansile mass in left ethmoidal sinuses which extends into left sphenoid sinus across the midline into the right ethmoidal sinus and extends down into the roof of the nasal cavity on the left. Erosion on the medial wall of left orbit, tissue planes around extra-ocular muscles and optical nerve at the apex of left orbit are blurred

The patient was urgently referred to a consultant maxillofacial surgeon near her home in Cardiff who ran a multi disciplinary team including ENT and neurosurgery.

Nasendoscopy biopsy of the left antrum undertaken in October 2010 revealed no malignant pathology. A re-biopsy was arranged and performed due to the invasive nature of the mass and confirmed a poorly differentiated carcinoma of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses and invasion of the cavernous sinus. The tumour was considered inoperable and was treated with chemo-radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy commenced in November 2010. This consisted of full dose cisplatin which is renally excreted, 75% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) at a reduced dose due to her primary biliary cirrhosis and uncertainty about liver reserve and omitted taxotere for the same reasons.

Chemotherapy was uneventful; however, on the last day of treatment she experienced abdominal pain of increasing intensity, which became a generalised abdominal tenderness over the following 24 hours. She was immediately transferred to the surgical team who performed a laparotomy and diagnosed an ischemic bowel and the operation was abandoned. Sadly, she died several hours later in the company of her family.

Discussion

Several key points have been raised by the management of this patient, which are important for primary and secondary care practitioners of medicine and dentistry. A morbid, but hidden tumour was left undiagnosed due to the unusual presentation of the patient's disease and an absence of clinically visible signs of pathology. Specific issues are discussed below.

Failure to correctly diagnose an antral tumour in the absence of clinical signs

Three presumptive diagnoses were made when the patient presented to her healthcare professionals in pain, these were trigeminal neuralgia, CIFP and sinusitis.

Common presenting complaints of trigeminal neuralgia include sudden, electric shock type pain triggered by specific points on a patient's face, conforming to the distribution of sensory nerve branches.3 Rarely is this condition associated with numbness or a tingling sensation, as presented by the patient in this case, or indeed by chronic pain.

Herpes zoster infection can present with excruciating neuropathic pain. The cluster of cranial nerve symptoms and signs, alongside the unrelated initial dermatomal involvement and the absence of vesicles affecting the head and neck would indicate that the patient's symptoms were unrelated to intra-current zoster, or a post-viral neuralgia.

CIFP can present as a nonspecific pain sometimes affecting the entire side of the face. It is a common problem affecting around 10% of adults and 50% of the elderly population and its inadequate recognition and management presents a burden to the health service. 95% of patients with CIFP complain of other symptoms, such as headache, neck and backache, dermatitis or pruritis, irritable bowel and dysfunctional uterine bleeding.4

It is essential that all patients are managed holistically and that a thorough history, clinical and radiographic examination as well as appropriate special tests are carried out which includes details of pain descriptors, pattern, severity and co-morbidities.5

A systematic history would have excluded a sinusitis as this would not necessarily present with tingling sensation over the side of her nose and palate, but as unilateral nasal blockage and pain on pressure over the infra-orbital or maxillary sinus region. Acute sinusitis may cause facial pain, whereas chronic sinusitis is unlikely to.6 This case draws attention to the importance of a forensic and systematic approach to elucidating a pain history, in particular in the absence of clinically visible signs of pathology.

Another valuable diagnostic procedure would have been a dental panoramic radiograph, which is commonly carried out in dental practice. Panoramic radiographs are worthy aids in the diagnosis of maxillary sinus pathology, including tumours and cystic lesions, which may appear as a loss of the radio-opaque outline of the maxillary sinus. Malignancies of the maxillary sinus frequently destroy the posterior wall of the sinus and it has been suggested that panoramic radiographs may be useful in the early detection of maxillary sinus carcinoma.7

A combination of the patient's symptoms and clinical signs would generate suspicion of maxillary sinus malignancy, including unilateral orofacial pain, nasal obstruction, epistaxis, diplopia and infra-orbital paraesthaesia warranting immediate referral to an appropriate specialist.2,6

Cranial nerve examination

This patient presented to her general healthcare professionals with facial numbness and loss of smell. A full cranial nerve examination (Table 1) would have indicated any other cranial nerve involvement as well as the extent of the cranial nerve distribution affected. The patient had lost olfactory and gustatory function (cranial nerves I and XII), all other cranial nerves were functioning and appeared intact including cranial nerve II as she had normal direct and consensual pupillary reflexes.

Chemotherapy and ischaemic bowel

The patient sadly died due to an ischaemic bowel which could not be salvaged. This was discovered by surgeons after she developed acute abdominal pain of increasing severity on the last day of her chemotherapy treatment. Over a 24 hours period she developed generalised abdominal tenderness and became hypotensive and tachycardic. It is unclear as to the exact cause of ischemic bowel in this instance, however, limited studies have linked certain chemotherapy regimens to acute vascular events. This has been linked to the hypothesis of splanchnic vasoconstriction or of a hypercoagulable state induced by the chemotherapy. It has been noted that in the event of acute abdominal pain developing soon after receiving chemotherapy, especially with regimens containing 5-FU, acute mesenteric ischaemia should be considered.9

A review of published studies revealed that 5-FU, cisplatin and vincristine have been associated with acute vascular events. Thrombotic occlusion of mesenteric arteries has been reported in two patients, which happened soon after the administration of these chemotherapy drugs.10

Conclusion

There is an obvious need for prompt investigation to include thorough history taking and appropriate investigations to eliminate possible organic disease such as a tumour when assessing CIFP. Treatment must be instigated to address the condition and not necessarily mask other symptoms. Vague peculiarity in clinical presentation can direct patients to seek care from several health professionals who provide different treatments with little collaboration, including dentists, doctors, neurologists, maxillofacial and ENT surgeons, osteopaths, chiropractors, and psychiatrists.4

This case report emphasises the need for early, co-ordinated and multi-disciplinary intervention by healthcare professionals, as well as appropriate referral when the presenting symptoms of facial pain are of unusual character and pointed to a sinister underlying malignancy.

References

Jham B C, Mesquita R A, Aguiar M C F, Vieira do Carmo M A. A case of maxillary sinus carcinoma. Oral Oncol Extra 2006; 42: 157–159.

Bhattacharyya N. Factors affecting survival in maxillary sinus cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61: 1016–1021.

Scully C, Felix D H. Oral medicine – update for the dental practitioner, orofacial pain. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 75–83.

Madland G, Feinmann C. Chronic facial pain: a multidisciplinary problem. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71: 716–719.

Aggarwal V R, McBeth J, Zakrzewska J M, Macfarlane G J. Unexplained orofacial pain – is an early diagnosis possible? Br Dent J 2008; 205: E6.

Bell G W, Joshi B B, Macleod R I. Maxillary sinus disease: diagnosis and treatment. Br Dent J 2011; 210: 113–118.

Epstein J B, Waisglass M, Bhimji S, Le N, Stevenson-Moore P. A comparison of computed tomography and panoramic radiography in assessing malignancy of the maxillary antrum. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1996; 32B: 191–201.

Scully C, Felix D H. Oral Medicine — update for the dental practitioner, disorders of orofacial sensation and movement. Br Dent J 2005; 199: 703–709.

Allerton R. Acute mesenteric ischaemia associated with 5-FU, cisplatin and vincristine chemotherapy. Clinical Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1996; 8: 116–117.

Okamoto T, Noguchi Y, Yoshikawa T et al. Chemotherapy-induced thrombotic occlusion of mesenteric arteries – case report and review of the literature. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1994; 21: 1279–1282.

Acknowledgements

This report is written in memory of Lyn Tompson-Dewey, whose strength and positivity were inspirational. We thank her family for allowing us to share this important story, so other patients may benefit from it in the future.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parmar, S., Chapple, I. Late diagnosis of an occult tumour – what lessons can we learn?. Br Dent J 212, 531–534 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.468

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.468

This article is cited by

-

Oral surgery II: Part 2. The maxillary sinus (antrum) and oral surgery

British Dental Journal (2017)