Abstract

The writing in carbonized Herculaneum scrolls, covered and preserved by the pyroclastic events of the Vesuvius in 79 AD, was recently revealed using X-ray phase-contrast tomography, without the need of unrolling the sensitive scrolls. Unfortunately, some of the text is difficult to read due to the interference of the papyrus fibers crossing the written text vertically and horizontally. Recently, lead was found as an elemental constituent in the writing, rendering the text more clearly readable when monitoring the lead X-ray fluorescence signal. Here, several hypotheses are postulated for the origin and state of lead in the papyrus writing. Multi-scale X-ray fluorescence micro-imaging, Monte Carlo quantification and X-ray absorption microspectroscopy experiments are used to provide additional information on the ink composition, in an attempt to determine the origin of the lead in the Herculaneum scrolls and validate the postulated hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the writing in rolled Herculaneum papyri was successfully explored by X-ray phase-contrast tomography1,2. These scrolls are part of a complete library, containing hundreds of such papyrus scrolls. This library was discovered between 1752 and 1754 in the small city of Herculaneum, which was covered and preserved by layers of volcanic material in 79 AD3,4,5,6. This is the only library passed on from Antiquity and is therefore an inestimable treasure. Due to the pyroclastic events associated with the eruption, the scrolls were carbonized and locked-up, rendering the writing on the scrolls unreadable. Previously, it was attempted to read these scrolls by mechanically unrolling them7. These attempts, however, usually led to the irretrievable loss of large parts of the text due to the brittle nature of the carbonized scrolls.

As demonstrated by the work of Mocella et al., the writing in the scrolls can now be, at least partially, recovered by non-destructive X-ray imaging methods, without the need of unrolling the scrolls1. The readability of the text is however not optimal due to interference of the papyrus fibres, running vertically and horizontally across the document. Recently, Brun et al. showed the presence of lead in the papyrus writing, rendering the text more readable when monitoring the Pb X-ray fluorescence (XRF) signal [Brun et al., submitted].

Several hypotheses to explain the presence of Pb and other elements in the sample are assessed using a sequence of non-destructive, X-ray based analytical techniques, providing further insights in the production and history of the Herculaneum manuscripts.

Lead could have been introduced unknowingly, or on purpose.

- An initial hypothesis is Pb contamination of the water used as a solvent for the ink.

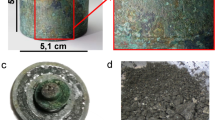

- A second hypothesis states that Pb could be present as a contaminant from a bronze container in which the ink was stored, as discussed by Canevali et al.8.

- Alternatively, Pb could have been knowingly introduced to the ink in a controlled fashion. Lead-based pigments, being a black mineral galena (PbS) or lead white (different mixtures of cerusite (PbCO3) and hydrocerusite (2PbCO3,Pb(OH)2)), were frequently used in ancient times as a pigment for cosmetic products9,10,11. Galena has been proposed as a pigment in black inks in Egyptian papyrus before12, whereas minium (Pb22+Pb4+O4) has been reported as a red pigment in Roman writing13,14.

- Additionally, Pb could originate from a binding medium in the ink: Pb compounds have been used extensively as dryers in paintings as they speed up the process of oil drying15,16. The use of litharge (PbO) as oil drier is already mentioned by Galen at the 2nd C. A.D. and by Marcellus at the 4th C. A.D17,18. Furthermore, the use of a lipid-based ink to draft the papyrus writing can be hypothesized8,19,20.

Results and Discussion

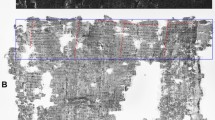

To be able to (dis)prove these hypotheses, two fragments (referred to as the “large” and “small” fragments) from unrolled scrolls were investigated. The two fragments are flat pieces of papyrus, made of different sheets and presenting E, Π, Ι, N, Ι, Α and O, Λ letters on their surface, respectively. A picture of the large sample is shown in Fig. 1A. In terms of analytical techniques, considering the precious nature of the samples, priority was given to non-destructive imaging methods. Besides, the heterogeneity of the samples at both micro- and millimetric scales motivated the implementation of a multi-scale analysis. Accordingly, macro and micro XRF and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) techniques were used, at ID2121 and BM26A22 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France). In order to have a good statistic record of XRF data in and out of the ink, XRF 2D maps were acquired over the full surface of the samples, with a sub-millimetre beam. As detailed in Brun et al. [submitted], the XRF map of Pb perfectly matches with the ink distribution (Fig. 1B) as the writing, faintly visible in Fig. 1A as well, is revealed. From this map, two average XRF spectra were extracted, by summing the pixel spectra corresponding to i) the writing using K-means clustering23 and visually comparing the clusters to the XRF distribution images, ii) the papyrus alone, excluding the written areas. The qualitative comparison of these two spectra reveals an increased concentration in Pb, Al and P in the written area, which is also observable on the XRF map (Supplementary Figure S1).

In order to quantitatively determine the ink composition, XRF results were simulated by means of Monte Carlo calculations24,25,26. These simulations model all relevant photon-matter interactions, simulating the trajectories of a large number of photons originating from an X-ray source and undergoing interactions in the sample, to the point of possible detection in a detector. The occurrence of each photon-matter interaction (photoelectric effect/fluorescence, Rayleigh and Compton scattering) as well as direction of propagation and distance between interactions of the photons are simulated. By iteratively comparing the simulated spectrum to its experimental equivalent and adjusting the simulated sample composition after each iteration, the experimental sample composition is determined.

Figure 1C shows the result of the Monte Carlo simulation based XRF spectrum. A clear correspondence is seen between the experimental spectrum and the theoretical simulation. The main differences are attributed to the lack of simulation for X-rays below 1 keV25 and a slight underestimation of the generated pulse pile-up (3.05 keV and >3.5 keV) due to the uncertainty on the simulated detector pulse width. Elemental concentrations are shown in Table 1. Both fragments show a similar C and Si content. The writing on the large fragment contains significantly more Pb and slightly more Na, Al, P and Cl. The S concentration is lower in the large fragment than in the small one. When comparing the quantification results of the writing to the papyrus of the same fragment, a characteristic increase in Al, P, Pb and in a lesser amount Cl is perceived, showing these elements are clearly associated with the writing. This was further investigated using μXRF, as discussed below (Fig. 2). Additionally, the papyrus in both fragments has a fairly similar composition, only Na and S quantities seem to vary. It should be noted that these quantification results do not represent the composition of the pure ink, but rather represent a mixture of the ink and the underlying papyrus due to the penetrating character of X-rays. Nevertheless, as the writing was mainly visible by the Pb signal, it is safe to say the Pb concentration calculated by the simulation can be mainly contributed to the ink and not the underlying papyrus. Taking into account the total area covered by the writing on each fragment and the average sample density, the Pb concentration in the ink is approximately 16 ± 5 μg/cm2 for the small and 84 ± 5 μg/cm2 for the large fragment.

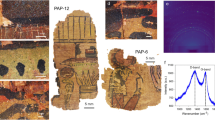

Micro-XRF Pb elemental distribution images on macroscopic (top left, 100 μm step size) to microscopic (bottom left, 1 μm step size) level. Red (P) Green (Al) Blue (S) images are displayed in the centre for different zoom modes (top right: 10 μm step size, bottom right: 1 μm step size) to display the co-localization of Al, P and S with Pb. Pb-P and Pb-S correlation plots are displayed to the right to show the correlation of Pb with P and partial correlation with S.

Based on the work of Kim et al.27 and Delile et al.28 it is clear these Pb contents are fairly high to be caused by the contamination of lead in the water (<1.5 mg/L), used as a solvent for the ink, or as a contaminant from a bronze container. Additionally, Cu was found to show no co-distribution with the writing on the papyrus, which would be expected if Pb in the writing was a contaminant from a bronze container (Supplementary Figure S2).

To obtain a better insight in the ink elemental composition, the same μXRF maps were acquired, but zooming on a particular part of the ink, with a smaller beam (down to sub-micrometric probe). It was of particular interest to see if elements, correlated at the millimetre scale, were also correlated at the micro-scale (hence potentially chemically associated). Figure 2 shows the Pb distribution on the large fragment on both macroscopic and microscopic levels, as well as the distribution of Al, P and S at different zoom levels down to the microscopic levels. It is clear from these results that Pb, P and Cl show a co-distribution (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Even though Al is co-localized with the Pb at the macro level (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figure S1), it is clear from the micro-scale images Pb is not chemically associated with Al due to their lack of co-distribution at the micro level. This demonstrates that the used ink has a complex composition, with different ingredients of which the distribution is homogeneous at the millimetre scale, but not at the microscopic level. The S signal shows a fairly homogeneous distribution over the papyrus, with occasional hot spots which are only partially co-distributed with Pb (Fig. 2). Taking into account the quantification results, it is thus unlikely that PbS is the main constituent of the papyrus ink.

Additionally, X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy was performed at the Pb-L3 and S-K edges to identify the chemical state and speciation of the Pb and S, by comparison with the XANES spectra of known compounds. Figure 3 displays the Pb-L3 XANES of the Pb in the writing, compared to several other reference compounds. It is clear from this image that Pb in the writing is in a state very similar to that of lead(II)acetate. Linear combination fitting of the papyrus data with the reference compound XANES shows there may be a partial contribution of PbS (up to 45%), along with lead(II)acetate. However, it should be noted the PbS XANES post-edge is fairly featureless; PbS contributes to the fit mainly to correct for a small edge shift and shaping of the post-edge feature at 13.085 keV compared to the lead(II)acetate reference. Comparing the papyrus writing Pb-L3 XANES curve with those measured for minium in literature29,30, it is clear no contribution of minium is found in the papyrus writing XANES due to the lack of contribution of the minium white line (~13.055 keV). As such, if minium was used to draft the writing, the compound was not preserved over the centuries.

As shown in Fig. 4, S-K edge XANES shows complex features, characteristic of a mixture of different species. The primary information is obtained by comparing the signal in and next to the ink. The spectra are quite similar, demonstrating that most of the signal in the area covered by the ink is most probably due to the papyrus behind the ink. The spectra exhibit features similar to those recorded on plants or wood, with both reduced and oxidized sulphur species. Cheah et al. discuss the speciation of sulphur in biochar, displaying a S-K edge XANES spectrum very similar to the one obtained from the papyrus and ink31. A good match for the reduced S contribution is found with an unknown organic sulphur compound as well as a sulphate, represented here as a dibenzothiophene and Ca-sulphate respectively, as in Cheah et al.31. More particularly, the presence of PbS in the papyrus writing is not indicated due to the absence of a sulphide peak at 2.4725 keV. A Cl-K edge XANES, measured on the writing, is shown to the right in Fig. 4. Based on comparison to reference materials available (among which PbCl2, NaCl, PVC) no match was found. However, comparison to literature shows that the probed Cl compound resembles organochlorine compounds as found in coal fuels32. Thus, despite the co-localization of Pb and Cl, they seem not directly chemically bonded in the papyrus ink.

Alternative to the use of a lead pigment, lead could have been introduced as a drier. As mentioned earlier, litharge was used in Antiquity as an oil drier17,18. As PbO is very prompt to react (e.g. with oil or another reactive), the detection of PbO “as is” is rendered improbable. Previous analyses including among others Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry and pyrolysis, applied to nine black powders found in Pompeii houses (possibly used as writing inks and cosmetics), revealed in eight samples the presence of lipids, of animal and/or plant origin7. The FTIR spectrum of one sample shows features characteristic of fatty soaps similar to those found in some Egyptian cosmetics9. The hypothesis of the Pb being present as lead carboxylates, consecutive to the use of a Pb-based drier and provided the organic lead species are original, is further strengthened by the Pb-L3 XANES as discussed above. Here, μFTIR was not attempted on the papyrus fragments as it would have required destruction of the sample. Therefore, information about organic components is rather limited. The distinction between a lead pigment and a lead drier can only be estimated based on the lead concentration in ink. A survey of several oil paint medium recipes from the XVth to the XXth century states the mass proportions of litharge-oil can vary from 1–4 to 1–1633. Using the latter fraction, an estimated writing thickness of 50 μm and an oil density of 0.93 g/mL, a theoretical concentration of 290 μg/cm2 of Pb is found. Concentrations obtained through the Monte Carlo quantification are lower (~80 μg/cm2). However, the actual ink layer thickness may be thinner than what was estimated here, as well as the proportion of the drier with respect to the “lead-based medium” could be lower. Additionally, the drying medium may have been diluted with other organic binders. It can also be argued that for Pb to originate from a pigment, the Pb concentration should be larger than Pb introduced via a drying agent. As such, the quantified Pb content is an additional argument for Pb originating from an admixture to the ink rather than the main constituent.

Finally, the presence of galena in the writing is discouraged by the S-K edge XANES and the only partial co-distribution of S and Pb at the micro-scale. However, it should be noted that PbS, if originally present, could have oxidized to PbO during the pyroclastic events that carbonized the scrolls. After the scrolls were discovered and exhumed in 17541,4,5,6 they were stored in wooden cabinets, which are known to exhume acetic acid vapours and can slowly react with PbO to form lead(II)acetate or other lead carboxylates34,35. This latter reaction scheme could also explain the presence of lead(II)acetate, or similar carboxylates, as found by the Pb-L3 XANES.

In conclusion, two Herculaneum papyrus fragments were investigated aiming at the non-destructive identification, localization, quantification and speciation of Pb by X-ray based techniques and Monte Carlo simulations. Several hypotheses were postulated towards the origin of the Pb in the scrolls and assessed using the aforementioned analytical techniques. Based on the Pb concentration and lack of co-distribution with Cu it was determined Pb is not originating from a contaminant in the ink solvent or container. The authors deem it more likely Pb was intentionally added to the ink, either as a pigment or as a drying agent. However, due to the changes the samples have likely undergone during the pyroclastic events and subsequent exhumation, the authors are unsuccessful at providing a definite answer to the question of the origin of Pb in the writing on the scrolls. Nevertheless, the applied analytical methodologies provide important insights in the manufacturing and history of these and similar precious artefacts and should be similarly applied to other papyri, preserved in better conditions. Moreover the found concentrations in these fragments provide important information for optimizing the future tomography experiments on the rolled-up Herculaneum scrolls. Further studies, in particular focusing on the speciation of organic compounds, may provide additional information required to form a definite answer to the origin of Pb in the scrolls, despite the often invasive nature of such techniques.

Methods

Description of the samples

The large fragment measures approximately 0.9 × 1.2 cm2, whereas the small fragment is approximately 0.5 × 0.8 cm2 large. Both samples are originating from unrolled scrolls and have an average thickness of approximately 0.3 mm. Samples were sandwiched in between two 4 μm thick ultralene foils (Spex, Certiprep).

XRF mapping acquisition

Microbeam measurements were performed at the X-ray microscopy beamline ID21 at the ESRF (Grenoble, France). The primary beam energy was tuned by the use of a Si(111) monochromator. To define the beam spot size on the sample for a general overview mapping, a pinhole (50 μm for the large fragment and 100 μm for the small fragment) was used. An incident beam flux monitoring pin diode was used continuously to correct for intensity variations. An average beam flux of 3.7 × 109 ph/s and 6.9 × 109 ph/s was obtained during the measurements on the large and small fragments respectively. The sample to detector chip distance was set to 3 cm and 3.1 cm for the large and small fragments, respectively. Scans were performed by moving the sample through the X-ray beam and acquiring an XRF spectrum at each step (38 × 31 100 μm steps for the small fragment and 160 × 175 50 μm steps for the large one). Acquisition times of 0.26 s and 1 s per step were used for the large and small fragments respectively. High resolution spatially resolved XRF measurements were performed using progressively smaller pixel size (10, 5 and 1 μm), the beam being focused down to ~0.3 × 0.6 μm2 using a Kirkpatrick-Baez mirror system.

The microscope is operated under vacuum and samples were placed under an angle of 62° with respect to the primary X-ray beam. The XRF (and scatter) radiation was detected using a Bruker (Germany) XFlash 5100 silicon drift detector (SDD), equipped with a Moxtek AP3.3 polymer window36, mounted under 69° with respect to the primary X-ray beam. An additional ultralene foil (4 μm) further covers the detector. XRF spectra were processed using PyMCA37 as well as the AXIL and IDL based Microxrf2 software packages38,39. Pixels contributing to the writing on the papyrus were isolated using K-means clustering routines, as incorporated in the Microxrf2 software23.

XRF quantification

The XRF data was quantified using Monte Carlo based simulations, as calculated by the XMI-MSIM simulation code24,25,26. Sample position and orientation as well as detector position and orientation were calculated based on the information as noted above. A detector active area of 0.8 cm2 was supplied without a collimator. Slits sizes were set to the size of the used pinhole. Additionally, the SDD detector crystal was simulated to consist of pure Si (ρ=2.33 g/cm3) with a 450 μm thickness. The primary X-ray beam was set to a monochromatic value of 3.5 keV with a 100% polarization in the horizontal plane. A source size equal to the pinhole size with a zero radian divergence was applied. The experimentally used 4 μm ultralene foils were approximated during the simulation as 4 μm Kapton polyimide foils, the composition of which was supplied by the built-in XMI-MSIM catalogue. Due to the small foil thickness and similar energy dependent X-ray absorption this approximation will not have a significant influence on the outcome of the quantification. The Moxtek AP3.3 window, consisting of a thin (<4 μm) polymer foil on top of a 100 μm or more silicon grid36, cannot be simulated in the XMI-MSIM program due to its heterogeneous nature. As 100 μm Si is virtually a beam stop to 3.5 keV X-ray photons (approximately 3 × 10−5% transmission), regions covered by the Moxtek window grid will not transmit photons to the detector. Provided a 70% open grid area, the Moxtek window Si grid was simulated in the XMI-MSIM program by reducing the initial X-ray beam flux by 30%. The live acquisition time corresponding to the writing sum spectrum was derived from the amount of pixels contributing to the writing and the acquisition time per point, taking into account an average dead time of 5% for the large and 15% for the small fragment. The sample thickness was estimated to be 300 μm and the sample density was calculated to be 0.36 g/cm3, based on the dimensions of the approximately cylindrical scroll with a diameter of 5 cm, length of 20 cm and weight of 141 g.

XAFS

Pb-L3 edge XAFS experiments were performed at the EXAFS station of the Dutch-Belgian beam line (DUBBLE, BM26A) at the ESRF (Grenoble, France)22. The energy of the X-ray beam was tuned using a Si(111) monochromator operating in fixed-exit mode, with an energy resolution of approximately 1.7 × 10−4 at 9.659 keV. Higher harmonics were rejected by using a vertically focusing Pt-coated mirror behind the monochromator. The primary X-ray beam was confined to 1(V) × 3(H) mm2 using a slit system and further focused down to approximately 20(V) × 60(H) μm2 at the sample position using polycapillary optics. The primary X-ray beam and transmitted beam intensities were monitored using ionization chambers, filled with a gas mixture to absorb approximately 10% and 70% of the beam respectively. The XRF/scattered radiation was detected using a Vortex-EM silicon drift detector.

XAFS energy scans were performed over the Pb-L3 edge (calibrated using a metallic Pb foil, setting the maximum of the first derivative to 13.035 keV), starting at E0 − 100 eV up to E0 + 100 eV. Acquisition times per energy step were chosen based on data statistics and available beam time. Additional XANES acquisitions were performed at ID21, at the sulphur and chlorine K-edges. XANES spectra were recorded in XRF mode (same set-up as above), with a beam of 50, 100 and 0.4 μm diameter. The monochromator was calibrated setting the maximum of absorption at 2.483 keV for CaSO4·2H2O reference and at 2.828 keV for NaCl reference. XANES were acquired from 2.46 to 2.58 keV with 400 steps of 0.3 eV at S K-edge and from 2.795 to 2.895 keV with 400 steps of 0.25 eV at Cl K-edge. Linear combination fitting of the XANES spectra was performed to identify and quantify mixtures of pure compounds, which were prepared as powder pressed to pellets and measured in transmission mode.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tack, P. et al. Tracking ink composition on Herculaneum papyrus scrolls: quantification and speciation of lead by X-ray based techniques and Monte Carlo simulations. Sci. Rep. 6, 20763; doi: 10.1038/srep20763 (2016).

References

Mocella, V., Brun, E., Ferrero, C. & Delattre, D. Revealing letters in rolled Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast imaging. Nat Commun 6, 5895, doi: 10.1038/ncomms6895 (2015).

Seales, W. B. & Delattre, D. virtual unrolling of carbonized herculaneum scrolls: research status (2007–2012). Cron Erc 43, 191–208 (2013).

Mattusch, C. C. & Lie, H. The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection. Getty Publications, doi: 10.1017/s0075435800001507 (2005).

Paderni, C. Extract of a letter from Signor Camillo Paderni, to Dr. Mead, concerning the Antiquities dug up from the ancient Herculaneum, dated from Naples. Philos. Trans. 48, 71–73 (1753).

Paderni, C. Extract of a letter from Camillo Paderni, keeper of the museum Herculaneum, to Thomas Hollis, Esq. Philos. Trans. 48, 634–638 (1754).

Paderni, C. Extract of a letter from Camillo Paderni, keeper of the Herculaneum museum, to Thomas Hollis, Esq., relating to the late discoveries at Herculaneum. Philos. Trans. 48, 821–825 (1753).

Delattre, D. Le point sur les travaux relatifs au PHerc. Paris 2. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 153-2, 925–943 (2009).

Canevali, C. et al. A multi-analytical approach for the characterization of powders from the Pompeii archaeological site. Anal Bioanal Chem 401, 1801–1814, doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5216-8 (2011).

Martinetto, P. et al. Synchrotron X-ray micro-beam studies of ancient Egyption make-up. Nucl. Instr. and Meth. in Phys. Rev. B 181, 744–748 (2001).

Cotte, M., Dumas, P., Richard, G., Breniaux, R. & Walter, P. New insight on ancient cosmetic preparation by synchrotron-based infrared microscopy. Anal. Chim. Acta 553, 105–110, doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.07.067 (2005).

Walter, P. et al. Making make-up in ancient Egypt. Nature 397, 483–484, doi: Doi 10.1038/17240 (1999).

Wagner, B. et al. Analytical approach to the conservation of the ancient Egyptian manuscript “Bakai Book of the Dead”: a case study. Microchim. Acta 159, 101–108, doi: 10.1007/s00604-007-0732-0 (2007).

Baraldi, P., Moscardi, G., Bensi, P., Aceto, M. & Tassi, L. An Investigation of the Palette and Techniques of Some High Medieval Codices by Raman Microscopy. Pigment and ink analysis of medieval codices, e-PS 6, 163–168 (2009).

Vornicu, N., Melniciuc-Puică, N. & Ardelean, E. Red Pigments Used for Writing and Illuminating Manuscripts. Scientific Annals of the Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi Orthodox Theology 1, 75–87 (2013).

Maroger, J. The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters Ch. 7–8 (Hacker Art Books, 1948).

Cotte, M. et al. Kinetics of oil saponification by lead salts in ancient preparations of pharmaceutical lead plasters and painting lead mediums. Talanta 70, 1136–1142, doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.03.007 (2006).

Kastens, M. L. & Hansen, F. R. Drier Soap Manufacture. Ind. Eng. Chem. 41, 2080–2090, doi: 10.1021/ie50478a008 (1949).

Sabin, A. H. Industrial and artistic technology of paint and varnish. Ch. 4, 36 (New York,: J. Wiley & Sons, Inc.; London,; Chapman & Hall, limited, 1927).

Winckelmann, J. J., Jansen, H., Brühl, H. & Barrois, L.-F. Recueil de lettres de M. Winckelmann, sur les découvertes faites à Herculanum, à Pompeii, à Stabia, à Caserte & à Rome. 350 (A Paris: Chez Barrois l’Aîné, libraire, quai des Augustins, 1784).

Boot, J. C. G. Notice sur les manuscrits trouvés à Herculanum. 78 (Amsterdam, J. Müller, 1841).

Salomé, M. et al. The ID21 Scanning X-ray Microscope at ESRF. J Phys Conf Ser. 425, 182004, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/425/18/182004 (2013).

Nikitenko, S. et al. Implementation of a combined SAXS/WAXS/QEXAFS set-up for time-resolved in situe xperiments. J Synchrotron Radiat 15, 632–640, doi: 10.1107/S0909049508023327 (2008).

Vekemans, B., Vincze, L., Brenker, F. E. & Adams, F. Processing of three-dimensional microscopic X-ray fluorescence data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 19, 1302–1308, doi: 10.1039/B404300f (2004).

Schoonjans, T. et al. The xraylib library for X-ray-matter interactions. Recent developments. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 66, 776–784, doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2011.09.011 (2011).

Schoonjans, T. et al. A general Monte Carlo simulation of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometers — Part 6. Quantification through iterative simulations. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 82, 36–41, doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2012.12.011 (2013).

Schoonjans, T. et al. A general Monte Carlo simulation of energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometers — Part 5. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 70, 10–23, doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2012.03.011 (2012).

Kim, E. J., Herrera, J. E., Huggins, D., Braam, J. & Koshowski, S. Effect of pH on the concentrations of lead and trace contaminants in drinking water: a combined batch, pipe loop and sentinel home study. Water Res. 45, 2763–2774, doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.02.023 (2011).

Delile, H., Blichert-Toft, J., Goiran, J. P., Keay, S. & Albarede, F. Lead in ancient Rome’s city waters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 6594–6599, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400097111 (2014).

Gabuda, S. P., Kozlova, S. G., Erenburg, S. B. & Bausk, N. V. XANES Pb LIII spectra of mixed-valence compound: Minium, Pb3O4. Nuclear Inst. and Methods in Physics Research, A 543, 184–187 (2005).

Figueiredo, M. O., Silva, T. P. & Veiga, J. P. A XANES study of the structural role of lead in glazes from decorated tiles, XVI to XVIII century manufacture. Appl. Phys. A 83, 209–211, doi: 10.1007/s00339-006-3509-0 (2006).

Cheah, S., Malone, S. C. & Feik, C. J. Speciation of sulfur in biochar produced from pyrolysis and gasification of oak and corn stover. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 8474–8480, doi: 10.1021/es500073r (2014).

Huggins, F. E. & Huffman, G. P. Chlorine in Coal - an Xafs Spectroscopic Investigation. Fuel 74, 556–569, doi: 10.1016/0016-2361(95)98359-M (1995).

de Viguerie, L., Ducouret, G., Cotte, M., Lequeux, F. & Walter, P. New insights on the glaze technique through reconstruction of old glaze medium formulations. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 331, 119–125, doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.07.037 (2008).

Niklasson, A., Johansson, L.-G. & Svensson, J.-E. The influence of relative humidity and temperature on the acetic acid vapour-induced atmospheric corrosion of lead. Corros. Sci. 50, 3031–3037, doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.08.009 (2008).

Arni, P. C., Cochrane, G. C. & Gray, J. D. The emission of corrosive vapours by wood. I. Survey of the acid-release properties of certain freshly felled hardwoods and softwoods. Journal of Applied Chemistry 15, 305–313 (1965).

Decker, K. W., Lines, M., Xu, D. & Perkins, R. Radiation Window With Coated Silicon Support Structure; Patent - US 7,709,820 B2. (2010).

Solé, V. A., Papillon, E., Cotte, M., Walter, P. & Susini, J. A multiplatform code for the analysis of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectra. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy 62, 63–68, doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2006.12.002 (2007).

Vekemans, B., Janssens, K., Vincze, L., Adams, F. & Vanespen, P. Analysis of X-Ray-Spectra by Iterative Least-Squares (Axil) - New Developments. X-Ray Spectrom. 23, 278–285, doi: 10.1002/xrs.1300230609 (1994).

Vekemans, B. et al. Automated Segmentation of l-XRF Image Sets. X-Ray Spectrom. 26, 333–346 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The ESRF is thanked for granting in-house beamtime. Authors thank C. Argoud for providing pictures of the samples and the Institut de France and the “Commission des Bibliothèques” for generously lending the papyrus samples. P. Tack is funded by a Ph.D. grant of the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT). The BM26A beamline staff is gratefully thanked for their on-going support in implementing the microfocus XRF/XAS setup. Great thanks also go out to J.P. Veiga and T. Silva for providing us with a minium Pb-L3 XANES spectrum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.T. wrote the manuscript and processed the ID21 and BM26A data, as well as participated in the BM26A experiments. M.C. ran the acquisition of XRF and XANES data at ID21, processed the XRF maps and participated in the interpretation of results and in writing the manuscript. S.B., W.B. and D.B. participated in the data acquisition of BM26A and assisted in optimizing the microfocus setup at BM26A. E.B., D.D. and V.M. assisted in the acquisition of XRF and XANES data at ID21 and participated in the interpretation of results and in writing the manuscript. C.F. participated in ID21 as well as BM26A data acquisition and assisted in the interpretation of results and in writing the manuscript. L.V. participated in the acquisition of BM26A data, interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tack, P., Cotte, M., Bauters, S. et al. Tracking ink composition on Herculaneum papyrus scrolls: quantification and speciation of lead by X-ray based techniques and Monte Carlo simulations. Sci Rep 6, 20763 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20763

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20763

This article is cited by

-

Layout of ancient Greek papyri through lead-drawn ruling lines revealed by Macro X-Ray Fluorescence Imaging

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Illustrating papyrus in Ancient Egypt

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A multidisciplinary study unveils the nature of a Roman ink of the I century AD

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Egyptian metallic inks on textiles from the 15th century BCE unravelled by non-invasive techniques and chemometric analysis

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

The nature of ancient Egyptian copper-containing carbon inks is revealed by synchrotron radiation based X-ray microscopy

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.