Abstract

Despite the recent emergence of enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), its clinical impact on adult population is less well defined. To better define the epidemiology of EV-D68, 6,800 nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) from 2010–2014 were subject to EV-D68 detection by RT-PCR and sequencing of 5′UTR and partial VP1. EV-D68 was detected in 30 (0.44%) NPAs from 22 children and 8 adults/elderlies. Sixteen patients (including five elderly) (53%) had pneumonia and 13 (43%) patients were complicated by small airway disease exacerbation. Phylogenetic analysis of VP1, 2C and 3D regions showed four distinct lineages of EV-D68, clade A1, A2, B1 and B3, with adults/elderlies exclusively infected by clade A2. The potentially new clade, B3, has emerged in 2014, while strains closely related to recently emerged B1 strains in the United States were also detected as early as 2011 in Hong Kong. The four lineages possessed distinct aa sequence patterns in BC and DE loops. Amino acid residues 97 and 140, within BC and DE-surface loops of VP1 respectively, were under potential positive selection. EV-D68 infections in Hong Kong usually peak in spring/summer, though with a delayed autumn/winter peak in 2011. This report suggests that EV-D68 may cause severe respiratory illness in adults/elderlies with underlying co-morbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, intensive research efforts have been made to identify novel causative agents of respiratory tract infections, leading to the discovery of various novel viruses including rhinovirus C (RV-C)1,2,3,4,5, human metapneumovirus6, human bocavirus (HBoV)7 and several novel coronaviruses, SARS coronavirus, human coronavirus NL63, human coronavirus HKU1 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. On the other hand, existing viruses have continued to emerge or re-emerge to cause respiratory disease epidemics.

Enteroviruses (EVs) are small, non-enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses that represent one of the 29 genera belonging to the family Picornaviridae. The genus now comprises 12 species, EV-A to EV-H, EV-J and rhinovirus A (RV-A) to RV-C (previously named human rhinovirus A to C)1,2,3,16,17, with >100 immunologically distinct serotypes. In addition, we have also recently described a novel EV species in dromedary camels18. EVs belonging to EV-A to EV-D and RV-A to RV-C cause a wide spectrum of diseases in humans3,19,20. EV-A71, one of the most pathogenic EVs, causes large-scale outbreaks of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) with high complication rates in Asia-Pacific region21,22. Other EVs may also have the potential to cause severe disease and deaths23.

EV-D68, a member of the species EV-D, has recently emerged in various countries. In contrast to other EVs which often cause systemic diseases such as HFMD, EV-D68 is mainly associated with respiratory tract infections. The virus was first isolated from throat swab samples of children with bronchiolitis and pneumonia in California in 1962 and referred as “Fermon virus”24. Rhinovirus 87 (RV87) and EV-D68 are now considered as the same virus with both RV and EV features (genetically related to other EVs but more temperature- and acid-labile)25,26. EV-D68 mainly affects infants, children and adolescents, while infections in adults were less commonly reported. Clinical manifestations of EV-D68 infections mainly resemble influenza-like illness, but life-threatening infections were also reported16,27,28,29,30,31. Neurological involvement, ranging from encephalomyelitis to acute flaccid paralysis, was rare, although a recent report highlighted possible association with acute flaccid myelitis16,32,33. Based on sequences of the viral capsid gene VP1, EV-D68 strains are often categorized into 3 distinct genetic groups, clade A to C, in addition to the original Fermon lineage29,33.

Subsequent to its first isolation, EV-D68 infections have only been rarely reported in the following decades. In US, only 26 cases of EV-D68 infections were detected by passive EV surveillance from 1970 to 200534. However, increasing reports of EV-D68 infections have recently been noted in various countries from Africa, America, Asia and Europe27,28,29,31,35,36,37. Since August 2014, more than 1000 cases of EV-D68 have been reported in the United States (US), with at least 14 potentially fatal cases31. In Hong Kong, unlike EV-A71 infection which is a notifiable disease, the prevalence of EV-D68 was largely unknown. However, a fatal case of EV-D68 was recently reported in a 10-year-old boy who presented with respiratory symptoms and complicated by encephalitis (http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/view_content/36405.html). To better define the disease impact and clinical spectrum of EV-D68, we examined the clinical and molecular epidemiology of EV-D68 among hospitalized patients with suspected respiratory virus infections in Hong Kong. The partial VP1, 2C and 3D genes of EV-D68 strains were sequenced to study the genetic diversity and evolutionary dynamics.

Results

Detection of EV-D68 from NPAs

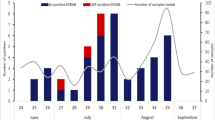

A total of 6800 NPAs were subject to EV detection by RT-PCR and sequencing of partial 5′UTR region. Samples positive for EVs were then subject to EV-D68 detection by RT-PCR and sequencing of VP1 region using EV-D68-specific primers. VP1 gene analysis showed that 30 (0.44%) NPAs were positive for EV-D68. The annual incidence rates were 0.27% (4/1500), 0.4% (6/1500), 0.62% (8/1300), 0.46% (6/1300) and 0.5% (6/1200) in year 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 respectively (Fig. 1). The peak season of EV-D68 usually occurred in late-spring/summer (May to August), except in 2011 when more cases were detected in late-autumn/early-winter (October to December).

Clinical characteristics of patients with EV-D68 infections

A bimodal age distribution was observed among the 30 patients (male: female = 19:11) with EV-D68 infections (Table 1), which included 22 children (<18 years), one 37-year-old adult and seven elderlies (>60 years). Of the seven elderlies, two resided in elderly homes (patients 19 and 23). A 15-year-old adolescent (patient 6) and a 37-year-old adult (patient 13) were also institutionalized. Close contacts of three patients were noted to have recent respiratory illnesses, including siblings of patients 3 and 4 and domestic helper of patient 28. One elderly (patient 20) had recent travel history to mainland China. No epidemiological linkage was identified among the 30 patients.

Twenty-two patients had underlying diseases, such as respiratory diseases and allergies. Most patients presented with acute respiratory illness. Sixteen patients (53%), including five elderlies, presented with pneumonia which represented the most common diagnosis. One elderly (patient 23) with pneumonia was complicated by congestive heart failure. Various radiological abnormalities were observed, including perihilar haziness, focal haziness, infiltrates and consolidation. Three patients (10%) presented with acute bronchiolitis or bronchitis. Exacerbations of small airway diseases were common, including asthmatic attacks (n = 13), febrile wheeze (n = 2) and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 2). Five patients (17%) presented with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), including a 63-year-old elderly (patient 21) who was complicated by acute coronary syndrome and shock. Another 2-year-old girl (patient 2) with acute bronchiolitis was complicated by intestinal obstruction. All patients recovered. Except for a 6-year-old girl (patient 29) with influenza C virus co-infection, no respiratory viruses or bacteria were identified from other patients.

Molecular epidemiology of EV-D68 circulating in Hong Kong

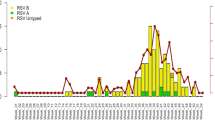

Phylogenetic analysis of partial VP1, 2C and 3D regions showed that the 30 EV-D68 strains fell into two major clades, clades A and B, corresponding to the two of the three EV-D68 clades described previously (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1)33,35. Previous studies have also revealed further subgroups, such as clade B1 and B2 among strains recently emerged in US30,33,38. Upon VP1 analysis, 15 strains belonged to clade B, some of which being closely related to recent B1 strains from US. Five strains detected in 2014 form a potentially new clade, B3, together with strains from Taiwan and mainland China. The other 15 strains belonged to clade A, which can be further divided into two subclades, A1 (n = 2) and A2 (n = 13). Analysis of 2C and 3D sequences showed similar clustering (Supplementary Fig. 1). The four circulating lineages, clade A1, A2, B1 and B3, shared ≥91.8% aa identities to each other in partial VP1 and displayed distinct amino acid polymorphisms in VP1, 2C and 3D (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic trees of the partial VP1 regions of EV-D68 strains in Hong Kong.

1004 nucleotide positions were included in the analysis. Strains detected in this study were marked with triangles. Strains detected during the epidemic in US in 2014 were highlighted in light gray. The tree was rooted with the original lineage including the prototype strain Fermon (Genbank accession no. AY426531). The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 50 bases.

The four clades appeared to dominate in different years. While both clade A1 and B1 were detected in 2010, clade A1 was not detected in subsequent years. Both clade A2 and B1 were co-circulating in 2011 and 2012. However, clade A2 and B was the only circulating lineage in 2013 and 2014 respectively. Moreover, A2 strains circulating in 2013 were clustered together, as with B3 strains in 2014 (Fig. 2), suggesting epidemics from specific lineages. The B3 strains were only distantly related to recent B1 strains in US, suggesting the recent emergence of this novel subclade. Interestingly, adults/elderlies infected by EV-D68 were exclusively associated with clade A2, including five closely related strains from elderlies in 2013. Closely related B3 strains were also noted in six children in 2014.

Detection of positive selection in VP1 genes

To assess adaptive evolution of EV-D68, dN/dS ratios (ω) in VP1 gene across the 30 strains were calculated on codon-by-codon basis. The overall ω was 0.077, with most residues having ω < 1, indicating purifying selection (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, residues 97 and 140 (within BC and DE-surface loops respectively) had ω > 1 but without statistical significance, indicating possible functional constraints during evolution. The dominant aa compositions at BC and DE-surface loops are shown in Fig. 4.

Relative residue abundance in the BC (a) and DE (b) surface-exposed loops of VP1 among lineage 1 and 2 strains. The graphical representation was generated using WebLogo. The height of symbol indicates the relative frequency of the corresponding amino acid. Amino acid position was based on the EV-D68 prototype strain Fermon.

Discussion

Our study represents the first to demonstrate EV-D68 as a possible cause of severe respiratory illness in adults or elderlies with underlying co-morbidities. In contrast to paediatric population, the role of EV-D68 in adult infections was less clear with only scarce reports. In the Netherlands, EV-D68-related respiratory illness has been described in adults but without clinical details27,29. Two reports from China have identified 13 and two adults respectively with URTIs due to EV-D6828,39. A recent report from Denmark identified EV-D68 infections in two adults with URTIs and one adult co-infected by RV with fever, cough and breathing difficulties30. In this study, only one elderly presented with URTI alone, while another elderly with URTI was complicated by acute coronary syndrome. The other five elderlies presented with pneumonia, with two having respiratory or cardiac complications. Another 37-year-old adult also presented with pneumonia. Our findings suggested that EV-D68 can cause severe infections in adults or elderlies with underlying diseases.

The EV-D68 infections in adults or elderlies may be underdiagnosed. The conserved 5′UTR is a common target for initial RT-PCR detection of EVs, while specific diagnosis of EV-D68 usually relies on specific RT-PCR assays or VP1 sequencing. In particular, a number of EV-D68 specific diagnostic tools based on real-time PCR assays have been developed recently40,41,42. Although commercially available multiplex PCR assays may include EV-D68, they may lack sensitivity and specificity and may not differentiate EV-D68 from RVs42. Moreover, EV-D68 is seldom included in diagnostic panels for respiratory viruses, while most surveillance programs for EVs focus on stool samples. Inclusion of EV-D68 in routine respiratory virus panels may also help better assess its clinical and public health significance.

The present study also represents the first to describe the epidemiology of EV-D68 infections in Hong Kong. The steady annual incidence observed suggested that EV-D68 has been circulating for at least several years. Unlike EV-A71 with seasonal peaks during summer/fall, as many as 50% of EV-D68 infections may fall outside usual EV peak seasons34,43,44. EV-D68 appears to peak during spring/summer in our population, while a delayed autumn/winter peak was observed in 2011. Therefore, factors other than temperature may also play a role in the seasonality of EV-D68 infection. Lower respiratory illness was common among both elderlies and children, with pneumonia being the most common diagnosis. Many patients were also complicated by exacerbation of small airway disease, in line with the disproportionate presence of asthma among cases in US45. Interestingly, a 2-year-old girl (patient 1) had hand-foot-mouth disease which has not been previously reported for EV-D68, although the possibility of co-infection by other EVs cannot be excluded. However, given the limited number of positive samples in this study, further epidemiology studies with inclusion of more cases are required to assess the seasonality, epidemiology and disease impact of EV-D68 in our population.

Our results revealed four lineages of EV-D68, A1, A2, B1 and B3, having circulated in our population and the potential emergence of a new subclade B3 in 2014. Moreover, adults/elderlies were infected exclusively by clade A2, suggesting that this lineage may be emerging in our elderly population. The recent emergence of EV-D68 in different countries may be due to viral evolution of strains/lineages with different antigenicity, with major bifurcation of currently circulating EV-D68 strains dated back to around 194533,35,39. The aa sequence patterns in BC and DE-surface loops, which determine the antigenic epitopes, may correlate with lineage classification35. The four lineages in this study also possessed distinct aa sequence patterns in BC and DE loops (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Moreover, most B strains circulating in 2014 formed a new separate subclade, B3, only distantly related to recent B1 sand B2 trains from US. Other potential B3 strains were also detected in Beijing and Taiwan in 2014 (Fig. 2). On the other hand, some of our B strains detected as early as 2011 were closely related to B1 strains from US. Our findings suggested that the recent epidemic in US may have originated from strains circulating in Asia several years ago, while a new lineage, B3, has only recently emerged in Hong Kong and neighbouring regions. More sequence data are needed to understand the genetic changes that may have driven the emergence of new lineages of EV-D68.

Different EVs are known to utilize difference receptors for cellular entry, which may explain their diverse clinical manifestations and tissue tropisms. In contrast to most EVs with enteric tropism, EV-D68 is seldom detected from stool of infected patients. Although EV-D68 possessed some properties of RVs, it does not utilize the receptors of RVs, namely intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) or low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R)46,47. Instead, it shares the same receptor, decay accelerating factor (DAF), with EV-D70 and several echovirus serotypes25,48,49. Interestingly, both EV-D68 and EV-D70 belong to the species EV-D, although EV-D70 is mainly associated with acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis19. In addition, EV-D68 may use sialic acids as receptor, with preferential binding α2–6-linked sialic acids (α2–6 SAs) than to α2–3 SAs, which may suggest higher affinity for upper respiratory epithelium47,50. Since our results suggest that lower respiratory illness can be common in EV-D68 infections, further studies are required to investigate if some strains or lineages may possess higher affinity for the lower airway.

Methods

Ethics statement

The ethical approval was given by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 04-278 T/600) and the study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Consents for the use of the clinical samples were waived because only left-over samples were used.

Patients and microbiological methods

All NPAs were collected from hospitalized patients in two regional hospitals in Hong Kong during a five-year period (January 2010 to December 2014) and were tested negative for influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses types 1, 2 and 3, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, human coronaviruses and human bocavirus2.

RT-PCR for detection of EV-D68 from NPAs

RNA extraction and RT-PCR for EVs were performed using previously described protocols with modifications and primers targeted to the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) as shown in Supplementary Table 12,51. Both strands of PCR products were sequenced twice with an ABI 3130xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), using the PCR primers. Nucleotide sequences were compared to those of known EVs with sequences available in GenBank. Positive samples with sequences belonging to EVs were subject to EV-D68 detection by RT-PCR and sequencing of VP1 gene using EV-D68 specific primers. Samples containing EV-D68 upon VP1 gene sequencing were further subject to 2C and 3D gene sequencing.

RT-PCR and sequencing of VP1, 2C and 3D gene regions

The partial VP1, 2C and 3D gene regions of EV-D68 strains detected from NPAs were amplified and sequenced using primers shown in Supplementary Table 1 and previously described protocols with modifications2,52. Phylogenetic trees of each region were constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) method in MEGA6, with bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates.

Selective pressure analysis

The number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site, dS and non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site, dN, in VP1 were calculated using Nei-Gojobori method (Jukes-Cantor) in MEGA5. Sites under positive selection were inferred using single-likelihood ancestor counting (SLAC) and fixed effects likelihood (FEL) methods as implemented in DataMonkey server (http://www.datamonkey.org). The overall ω (dN/dS) value was calculated according to NJ trees under the TrN93 substitution model. Positive selection for a site was considered to be statistically significant if P-value was <0.1. A mixed-effects model of evolution (MEME) was further used to identify positively selected sites under episodic diversifying selection in particular positions among different clades within a phylogenetic tree even when positive selection is not evident across the entire tree. The relative residue abundance within BC and DE-surface exposed loops were depicted using WebLogo.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The sequences of EV-D68 strains have been lodged within GenBank under accession no. KT959173-KT959202 (VP1), KT959113-KT959142 (2C) and KT959143-KT959172 (3D).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lau, S. K. P. et al. Enterovirus D68 Infections Associated with Severe Respiratory Illness in Elderly Patients and Emergence of a Novel Clade in Hong Kong. Sci. Rep. 6, 25147; doi: 10.1038/srep25147 (2016).

References

McErlean, P. et al. Characterisation of a newly identified human rhinovirus, HRV-QPM, discovered in infants with bronchiolitis. J Clin Virol 39, 67–75, doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.012 (2007).

Lau, S. K. et al. Clinical features and complete genome characterization of a distinct human rhinovirus (HRV) genetic cluster, probably representing a previously undetected HRV species, HRV-C, associated with acute respiratory illness in children. J Clin Microbiol 45, 3655–3664, doi: 10.1128/JCM.01254-07 (2007).

Lau, S. K. et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus C in children and adults in Hong Kong reveals a possible distinct human rhinovirus C subgroup. J Infect Dis 200, 1096–1103, doi: 10.1086/605697 (2009).

Lamson, D. et al. MassTag polymerase-chain-reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004–2005. J Infect Dis 194, 1398–1402, doi: 10.1086/508551 (2006).

Kistler, A. et al. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J Infect Dis 196, 817–825, doi: 10.1086/520816 (2007).

van den Hoogen, B. G. et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med 7, 719–724, doi: 10.1038/89098 (2001).

Allander, T. et al. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 12891–12896, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102 (2005).

Peiris, J. S. et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361, 1319–1325 (2003).

Fouchier, R. A. et al. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 6212–6216, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400762101 (2004).

van der Hoek, L. et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med 10, 368–373, doi: 10.1038/nm1024 (2004).

Lau, S. K. et al. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol 44, 2063–2071, doi: 10.1128/JCM.02614-05 (2006).

Woo, P. C. et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol 79, 884–895, doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005 (2005).

Woo, P. C. et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1-associated community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis 192, 1898–1907, doi: 10.1086/497151 (2005).

Zaki, A. M., van Boheemen, S., Bestebroer, T. M., Osterhaus, A. D. & Fouchier, R. A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367, 1814–1820, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 (2012).

de Groot, R. J. et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol 87, 7790–7792, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-13 (2013).

Tapparel, C., Siegrist, F., Petty, T. J. & Kaiser, L. Picornavirus and enterovirus diversity with associated human diseases. Infect Genet Evol 14, 282–293, doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.016 (2013).

Knowles, N. J. et al. Picornaviridae. In: Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. ed.: King, A. M. Q., Adams, M. J., Carstens, E. B. & Lefkowitz, E. J. San Diego: Elsevier, 855–880 (2012).

Woo, P. C. et al. A novel dromedary camel enterovirus in the family Picornaviridae from dromedaries in the Middle East. J Gen Virol 96, 1723–1731, doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000131 (2015).

Pallansh, M. A. O. M. & Whitton, J. L. Enteroviruses: Polioviruses, Coxackiviruses, Echoviruses and Newer Enteroviruses. Ch 17 Field’s Virology 6th edition. Copyright 2013© Wolters Kluwer LWW (2013).

Lau, S. K. et al. Detection of human rhinovirus C in fecal samples of children with gastroenteritis. J Clin Virol 53, 290–296, doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.01.008 (2012).

Ho, M. et al. An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. Taiwan Enterovirus Epidemic Working Group. N Engl J Med 341, 929–935, doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411301 (1999).

Wang, R. Y. et al. Proteome demonstration of alpha-1-acid glycoprotein and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin candidate biomarkers for diagnosis of enterovirus 71 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 34, 304–310, doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000534 (2015).

Yip, C. C. et al. Recombinant coxsackievirus A2 and deaths of children, Hong Kong, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 19, 1285–1288, doi: 10.3201/eid1908.121498 (2013).

Schieble, J. H., Fox, V. L. & Lennette, E. H. A probable new human picornavirus associated with respiratory diseases. Am J Epidemiol 85, 297–310 (1967).

Blomqvist, S., Savolainen, C., Raman, L., Roivainen, M. & Hovi, T. Human rhinovirus 87 and enterovirus 68 represent a unique serotype with rhinovirus and enterovirus features. J Clin Microbiol 40, 4218–4223 (2002).

Savolainen, C., Blomqvist, S., Mulders, M. N. & Hovi, T. Genetic clustering of all 102 human rhinovirus prototype strains: serotype 87 is close to human enterovirus 70. J Gen Virol 83, 333–340, doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-2-333 (2002).

Rahamat-Langendoen, J. et al. Upsurge of human enterovirus 68 infections in patients with severe respiratory tract infections. J Clin Virol 52, 103–106, doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.06.019 (2011).

Xiang, Z. et al. Coxsackievirus A21, enterovirus 68 and acute respiratory tract infection, China. Emerg Infect Dis 18, 821–824, doi: 10.3201/eid1805.111376 (2012).

Meijer, A. et al. Emergence and epidemic occurrence of enterovirus 68 respiratory infections in The Netherlands in 2010. Virology 423, 49–57, doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.021 (2012).

Midgley, S. E., Christiansen, C. B., Poulsen, M. W., Hansen, C. H. & Fischer, T. K. Emergence of enterovirus D68 in Denmark, June 2014 to February 2015. Euro Surveill 20 (2015).

Midgley, C. M. et al. Severe respiratory illness associated with enterovirus D68 - Missouri and Illinois, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63, 798–799 (2014).

Pfeiffer, H. C. et al. Two cases of acute severe flaccid myelitis associated with enterovirus D68 infection in children, Norway, autumn 2014. Euro Surveill 20, 21062 (2015).

Greninger, A. L. et al. A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA (2012–14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15, 671–682, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70093-9 (2015).

Khetsuriani, N. et al. Enterovirus surveillance–United States, 1970–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ 55, 1–20 (2006).

Linsuwanon, P. et al. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of human enterovirus serotype 68 in Thailand, 2006–2011. PLos One 7, e35190, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035190 (2012).

Xiao, Q. et al. Prevalence and molecular characterizations of enterovirus D68 among children with acute respiratory infection in China between 2012 and 2014. Sci Rep 5, 16639, doi: 10.1038/srep16639 (2015).

Poelman, R. et al. European surveillance for enterovirus D68 during the emerging North-American outbreak in 2014. J Clin Virol 71, 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.07.296 (2015).

Tan, Y. et al. Molecular Evolution and Intraclade Recombination of Enterovirus D68 during the 2014 Outbreak in the United States. J Virol 90, 1997–2007, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02418-15 (2015).

Lu, Q. B. et al. Detection of enterovirus 68 as one of the commonest types of enterovirus found in patients with acute respiratory tract infection in China. J Med Microbiol 63, 408–414, doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.068247-0 (2014).

Zhuge, J. et al. Evaluation of a Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay for Detection of Enterovirus D68 in Clinical Samples from an Outbreak in New York State in 2014. J Clin Microbiol 53, 1915–1920, doi: 10.1128/JCM.00358-15 (2015).

Bragstad, K. et al. High frequency of enterovirus D68 in children hospitalised with respiratory illness in Norway, autumn 2014. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 9, 59–63, doi: 10.1111/irv.12300 (2015).

Jaramillo-Gutierrez, G. et al. September through October 2010 multi-centre study in the Netherlands examining laboratory ability to detect enterovirus 68, an emerging respiratory pathogen. J Virol Methods 190, 53–62, doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.02.010 (2013).

Centers for Disease, C. & Prevention. Clusters of acute respiratory illness associated with human enterovirus 68–Asia, Europe and United States, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60, 1301–1304 (2011).

Hasegawa, S., Hirano, R., Okamoto-Nakagawa, R., Ichiyama, T. & Shirabe, K. Enterovirus 68 infection in children with asthma attacks: virus-induced asthma in Japanese children. Allergy 66, 1618–1620, doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02725.x (2011).

Midgley, C. M. et al. Severe respiratory illness associated with a nationwide outbreak of enterovirus D68 in the USA (2014): a descriptive epidemiological investigation. Lancet Respir Med 3, 879–887, doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00335-5 (2015).

Hofer, F. et al. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91, 1839–1842 (1994).

Uncapher, C. R., DeWitt, C. M. & Colonno, R. J. The major and minor group receptor families contain all but one human rhinovirus serotype. Virology 180, 814–817 (1991).

Smura, T. et al. Cellular tropism of human enterovirus D species serotypes EV-94, EV-70 and EV-68 in vitro: implications for pathogenesis. J Med Virol 82, 1940–1949, doi: 10.1002/jmv.21894 (2010).

Karnauchow, T. M. et al. The HeLa cell receptor for enterovirus 70 is decay-accelerating factor (CD55). J Virol 70, 5143–5152 (1996).

Imamura, T. et al. Antigenic and receptor binding properties of enterovirus 68. J Virol 88, 2374–2384, doi: 10.1128/JVI.03070-13 (2014).

Yip, C. C. et al. Emergence of enterovirus 71 “double-recombinant” strains belonging to a novel genotype D originating from southern China: first evidence for combination of intratypic and intertypic recombination events in EV71. Arch Virol 155, 1413–1424, doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0722-0 (2010).

Brown, B., Oberste, M. S., Maher, K. & Pallansch, M. A. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid coding region. J Virol 77, 8973–8984 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the generous support of Mrs. Carol Yu, Professor Richard Yu, Mr. Hui Hoy and Mr. Hui Ming in the genomic sequencing platform. This work was partly supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund HKM-15-M02, Food and Health Bureau, HKSAR; Strategic Research Theme Fund, Committee for Research and Conference Grant and University Development Fund, The University of Hong Kong; Croucher Senior Medical Research Fellowships; National Science and Technology Major Project of China 2012ZX10004213; and Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Disease for Department of Health, HKSAR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K.P.L. and P.S.-H.Z. wrote the manuscript. S.K.P.L., C.C.Y.Y. and P.S.-H.Z. analyzed data. C.C.Y.Y., P.S.-H.Z. and W.-N.C. performed experiments. S.K.P.L., K.K.W.T., A.K.L.W., K.-Y.Y. and P.C.Y.W. collected clinical samples and data.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, S., Yip, C., Zhao, PH. et al. Enterovirus D68 Infections Associated with Severe Respiratory Illness in Elderly Patients and Emergence of a Novel Clade in Hong Kong. Sci Rep 6, 25147 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25147

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25147

This article is cited by

-

Clinical and molecular epidemiologic features of enterovirus D68 infection in children with acute lower respiratory tract infection in China

Archives of Virology (2023)

-

Upsurge of Enterovirus D68 and Circulation of the New Subclade D3 and Subclade B3 in Beijing, China, 2016

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

A cross-sectional seroepidemiology study of EV-D68 in China

Emerging Microbes & Infections (2018)

-

Amplification and next generation sequencing of near full-length human enteroviruses for identification and characterisation from clinical samples

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Enterovirus D68 Subclade B3 Strain Circulating and Causing an Outbreak in the United States in 2016

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.