Abstract

Revenue recycling through lump-sum dividends may help mitigate public opposition to carbon taxes, yet evidence from real-world policies is lacking. Here we use survey data from Canada and Switzerland, the only countries with climate rebate programmes, to show low public awareness and substantial underestimation of climate rebate amounts in both countries. Information was obtained using a five-wave panel survey that tracked public attitudes before, during and after implementation of Canada’s 2019 carbon tax and dividend policy and a large-scale survey of Swiss residents. Experimental provision of individualized information about true rebate amounts had modest impacts on public support in Switzerland but potentially deleterious effects on support in Canada, especially among Conservative voters. In both countries, we find that perceptions of climate rebates are structured less by informed assessments of economic interest than by partisan identities. These results suggest limited effects of existing rebate programmes, to date, in reshaping the politics of carbon taxation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In recent years, over 3,500 US economists, including 27 Nobel prize winners1, and 1,600 European economists2 have signed public statements advocating carbon taxation. As a policy tool, carbon taxes offer theoretical cost effectiveness, price stability and administrative simplicity. However, these potential economic advantages can come with a steep political price. Carbon taxes have been rejected in referenda and elections3,4,5,6,7, been reversed after political backlash8,9, been opposed by a substantial proportion of the public10,11,12 and generated political controversy whenever debated across advanced democracies9,11,13,14,15,16. Scholars have identified diverse barriers to public acceptance of carbon taxes, including perceptions that the policy will not reduce emissions, that it is too costly, that it is regressive and that it might undermine economic prosperity10,11,17,18,19,20.

In response to this opposition, interest has grown in deploying carbon tax revenues to boost public support. Carbon tax revenues can be directed towards environmental spending4,6,7,17,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 or can be paired with tax cuts, although this latter approach may be less effective than green spending at reducing public opposition23,24,28,30,31 or only effective for some voters22,32,33. However, earmarking through either spending or tax cuts may lack high visibility6,34, and voters may distrust that governments will deliver or maintain these benefits23,33,35,36. Instead, it has been suggested that highly visible lump-sum rebates or ‘dividends’ could be more effective in winning public support and reinforcing that support over time as beneficiaries become accustomed to regular dividends37. The hypothetical potential of climate rebates to increase public carbon pricing support has been shown in the United States4,17,20,21,29, Canada38, Norway35, Switzerland39, the United Kingdom4,30, Australia4, Germany17, Turkey27, France40 and India4. These studies offer strong reasons to expect that bundling carbon taxes with lump-sum rebates could increase public acceptance.

However, other studies offer more sobering assessment. Surveys measuring public support for hypothetical policies may overestimate voters’ support when confronted with real-world costs. For example, polling overestimated voter support for failed carbon tax referenda in Washington state5 and Switzerland39. Voters’ perceptions of rebate costs and benefits may also be shaped by competing partisan and interest-group narratives5,40,41. More broadly, voters are often unaware they receive even high-profile government benefits42.

In light of these competing perspectives, the political impact of climate rebates requires testing in the context of real-world policies, as they are implemented. Two such policies currently exist, in Canada and Switzerland. In Canada, the federal government imposed a carbon tax and rebate scheme for households as part of its national strategy for pricing carbon in 2019, which currently applies in four of the country’s ten provinces (covering over half of the Canadian population). The tax was initially set at 20 Canadian dollars (Can$20) per tonne, rising to Can$50 per tonne by 2022. In December 2020, the government announced a revised schedule increasing to Can$170 per tonne by 2030. The associated rebate, called the Climate Action Incentive Payment, is based on the number of adults and children in each household, with a 10% increase for rural households. It is delivered through an income tax credit to one adult per household. All tax revenues are returned to the province of origin. Because provincial emissions per capita vary widely, rebate sizes also vary by province. For example, the average dividend in Saskatchewan is almost double that in Ontario. The policy is highly progressive, with 80% of households receiving more in dividends than they pay in carbon taxes43. Supplementary Section 1 details Canadian federal and provincial carbon pricing.

By contrast, Switzerland established its climate rebate programme in 2008 as part of an escalating carbon tax that reached 96 Swiss francs (CHF96) per tonne by 2018. In Switzerland, roughly two-thirds of revenue is redistributed to businesses and the public. Public rebates are given on a per capita basis, with every person (including children) receiving an equal amount. Citizens receive their rebates as a discount on their health insurance premiums, with annual notifications about this monthly benefit through health insurance forms. In a June 2021 referendum, Swiss voters narrowly rejected a climate law that would have increased the carbon tax level and associated rebate amounts. Supplementary Section 2 details the Swiss policy context.

We evaluate the effect of real-world dividends on public support for carbon taxes in both countries. In Canada, we report an original five-wave panel survey of Canadians from February 2019 to May 2020. Our sample included residents from five provinces, two subject to the federal carbon tax (Saskatchewan and Ontario), one with provincial emissions trading (Quebec) and two with provincial carbon taxes (British Columbia and Alberta). Alberta repealed its provincial tax midway through our study, prompting introduction of a federal-tax and rebate scheme in 2020. We surveyed the same respondents after the federal carbon tax was announced but before it was implemented (February 2019), soon after implementation (April 2019), after residents of federal-tax provinces received their rebates (July 2019), after a federal election in which carbon pricing was a prominent issue (November 2019) and one year after policy implementation (May 2020). In wave 4, we embedded a survey experiment exposing respondents to individualized information about their actual rebates. In Switzerland, we fielded a survey of 1,050 Swiss residents in December 2019, which also included an embedded survey experiment where respondents were exposed to information on their actual policy rebates. We provide full details on Canadian and Swiss surveys in Methods.

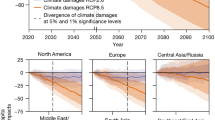

We begin with data from our longitudinal Canadian survey, visualizing public support for carbon pricing by province over time (Fig. 1). Canadian carbon tax support remained relatively stable across our panel. In the rebate province of Ontario, public support by wave 5 was within two percentage points of wave 1. However, between waves 1 and 4, carbon pricing support did increase in the rebate province of Saskatchewan, before declining through wave 5 for a net gain of five percentage points to 32%. The final wave followed the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, although COVID incidence in rebate provinces was still low; for example, in Saskatchewan, there had been a total of only 176 cases and 2 COVID-related deaths in advance of wave 5 (ref. 44). Federal COVID-related financial assistance was already available to respondents by this time. Trends in carbon pricing opposition are similar (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Section 4). We also conduct exploratory statistical analysis comparing trends in rebate versus non-rebate provinces (Supplementary Section 5).

The dotted line indicates when the federal carbon tax policy came into effect. The solid line indicates the approximate period during which households received their climate rebates. The dashed line indicates the timing of a federal election in which the carbon tax was highly salient. Respondents in Saskatchewan and Ontario received climate rebates. Data from respondents who completed all five waves (n = 899). Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals. Supplementary Section 3 reproduces this figure for the first four waves only (n = 1,190), finding identical trends across this expanded sample.

These provincial averages mask strong partisan differences in carbon pricing support (Fig. 2). Policy support was concentrated among Liberal Party of Canada supporters (the party that implemented the policy) versus Conservative Party of Canada supporters (the opposition party that strongly opposed it) and remained stable through time. Conservative opposition persisted in both federal-tax (rebate) and provincial pricing (non-rebate) provinces. By wave 5, 75% and 81% of Liberal Party supporters in Ontario and Saskatchewan, respectively, supported carbon pricing, compared with 32% and 13% of Conservative Party supporters in these same provinces. Partisan splits across rebate and non-rebate provinces show similar trends (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Section 6). These partisan differences persist even after conditioning on respondents’ individual cost exposure (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Section 7).

The dotted line indicates when the policy came into effect. The solid line indicates the approximate period during which households received their climate rebates. The dashed line indicates the timing of a federal election in which the carbon tax was highly salient. Voters are classified according to their wave 1 (pre-policy implementation) party preferences. Albertan respondents are excluded because Alberta switched from being a non-rebate province to being a rebate province between waves 1 and 5. Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals.

For rebate policies to offer political benefits to incumbent governments, the public must perceive those benefits42,45. We test public knowledge about existing rebate programmes in both Canada and Switzerland. We first test Canadian respondents’ specific knowledge about their rebates. In wave 3, immediately after residents of Ontario and Saskatchewan received their rebates, we asked respondents whether they had received a climate-related benefit as part of their federal income tax returns (Supplementary Section 8). Many Canadians did not know, including 17% in rebate provinces and between 33% and 36% in non-rebate provinces. In Ontario, only 55% of residents correctly believed they had received a rebate, while Saskatchewan residents were more aware (75%). By contrast, about 11% and 13% of individuals in the non-rebate provinces of Alberta and British Columbia incorrectly reported rebate receipt.

We then asked respondents to estimate the size of any rebate they believed their household had received (Table 1). We compare perceived amounts to the true average rebate for our survey respondents (see Methods for details). Residents in non-rebate provinces nonetheless estimated a positive average rebate amount, a misperception that continued after the fall 2019 election (Supplementary Section 9). In rebate provinces, our survey averages reflect a 40% underestimation in Saskatchewan and 32% underestimation in Ontario of true rebate amounts. Limiting our analysis to respondents who correctly believed they had received a rebate, the Ontario average estimate was CDN$198 (standard error (s.e.) $13), only a 9% underestimation, and the Saskatchewan average estimate was CDN$315 (s.e. $13), a 29% underestimation. Still, only 24% of Ontario respondents and 19% of Saskatchewan respondents estimated a rebate amount falling within CDN$100 of their true rebate (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Section 10). These misperceptions are associated with party preference. In both provinces, respondents who consistently indicated they would vote for the anti-carbon tax Conservative Party systematically estimated lower rebate amounts (Supplementary Section 10). We also find persistent confusion among respondents as to whether the provincial or federal government is responsible for carbon pricing in their province, with some learning across the panel (Supplementary Section 11).

We conduct a similar analysis in Switzerland. Consistent with previous surveys7,46, we find limited knowledge of the Swiss rebate policy. Although the policy has been in place for over ten years, only 12% of respondents knew tax revenues were redistributed to the public, and 85% did not know they received a health bill discount associated with the country’s carbon tax (Fig. 3). Every Swiss resident receives CHF5.35 per month (in 2019) as their rebate, but only 13% of respondents knew (or correctly guessed) the monthly rebate was between CHF3 and CHF10.

a–d, Responses to survey questions: belief that Switzerland has a carbon tax on fossil fuels (a), belief regarding what most carbon tax revenue is directed towards (b), belief regarding what tax revenue is redistributed to reduce (c), perceived monthly rebate size (d). Correct choices are highlighted in green.

Low public awareness of rebates in Canada and Switzerland may stem from the indirect mechanisms through which governments in both countries redistribute their climate dividends. Using two survey experiments, we assess whether increasing rebate awareness through individualized rebate information increases support for existing and future carbon taxes. Here, low existing public knowledge allows us to randomize information about government benefits that respondents already receive, providing a second-best approximation for experimental manipulation of rebate receipt itself. However, our experiments ultimately identify the effect of information about rebates on public support, not the direct effect of rebates themselves. These experiments also focus on testing information about policy benefits, rather than policy costs.

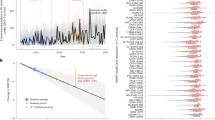

In Canada, half of wave 4 survey respondents from Ontario and Saskatchewan (n = 605) were randomly assigned a custom mock-up of their own tax return with their true climate dividend prominently displayed (Supplementary Section 12 describes treatment; Methods describes calculation details; Supplementary Section 13 shows experimental balance.) Receiving treatment led respondents to increase perceptions of their household’s rebate size, suggesting at least partial updating in the treatment group (Supplementary Section 14). However, treatment did not change carbon pricing support (Fig. 4a: Difference-in-Means (DIM) = –0.0342, s.e. = 0.106, P = 0.747). Instead, information about their true benefit decreased respondents’ belief that the rebates were sufficient to cover their tax exposure (Fig. 4b: DIM = –0.136, s.e. = 0.0662, P = 0.0398). As such, Canadians who learned the true value of their rebates were significantly more likely to perceive themselves as net losers even though most Canadians are net beneficiaries. This shift was concentrated among Conservative Party of Canada supporters (DIM = –0.213, s.e. = 0.102, P = 0.0391).

a,b, Exposure to individualized information about a respondent’s true climate rebate amount in Canada did not shape carbon pricing support (a) but instead generated a backlash by making respondents believe they paid more in tax than they received as their rebate (b). Full sample is in black, with subgroups defined by wave 4 party preference. Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals. NDP, New Democratic Party.

In our December 2019 Switzerland survey, half of respondents were randomly assigned an encouragement treatment to leave their computers mid-survey and retrieve their health insurance forms; respondents were then asked to report the size of their benefit. All treated respondents were then shown a sample health form with benefit size highlighted (Supplementary Section 15 provides example), irrespective of whether they reported having found their personal form (Supplementary Section 16 shows experimental balance). Unlike in Canada, we find personal rebate information increased support for the current scheme on a four-point scale by around one-fifth of a standard deviation (DIM = 0.18885, s.e. = 0.06155, P < 0.01; Fig. 5a). These results hold on both the right and left sides of the political spectrum but not for centre-party supporters. However, treatment had no effect on support for either small (equivalent to CHF0.03 per litre increase in heating oil costs; DIM = 0.06213, s.e. = 0.09744, P = 0.524) or large (equivalent to CHF0.15 per litre increase in heating oil costs; DIM = 0.11182, s.e. = 0.09396, P = 0.235) increases in the Swiss carbon tax rate.

a–c, Exposure to individualized information about a respondent’s true climate rebate amount in Switzerland increased support for the existing policy (a) but not support for either small (b) or large (c) future carbon tax increases. Full sample in black, with subgroups based on ideological position of preferred political party (Supplementary Section 17 provides classification details). Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals.

Beyond low visibility, we also consider alternative reasons for the weak effects of rebates on public opinion. In Canada, carbon pricing preferences might have remained relatively stable despite rebates because the political benefits of revenue recycling came with policy announcement (before our wave 1), not during implementation (our panel period). Two pieces of evidence suggest this as unlikely. First, we find little baseline knowledge about the rebate in wave 1, which we would expect if anticipation of future rebates had already increased support (Supplementary Section 11). Second, the announcement of a federal rebate policy for Alberta occurred between waves 2 and 3, after a newly elected provincial government repealed the provincial tax, which did not provide universal rebates. This prompted the federal government to step in to announce it would impose a tax and rebate policy over the objection of the provincial government (as in Saskatchewan and Ontario.) However, we find no announcement effect in Alberta, where carbon pricing support trends roughly in parallel with other provinces after policy announcement (Fig. 1).

Another possibility is that policy preferences remain conditioned primarily by partisanship. We find that Conservative Party supporters are more likely than Liberal Party supporters to acknowledge having seen negative ads about carbon pricing and to report that these ads made them less supportive of this policy (Supplementary Section 18). Similarly, respondents who report having voted for the Conservative Party in the Fall 2019 election were more likely to underestimate their rebates, even when exposed to information about their true rebate amount in our survey experiment (Supplementary Section 19). More broadly, in the two federal-tax provinces, supporters of the Liberal Party of Canada were three to eight times more likely to support the carbon tax than were Conservative Party supporters. Similarly, in Switzerland, left-leaning voters were 48% more likely to support rebates relative to right-leaning voters. In short, partisanship does structure both carbon tax preferences and patterns of rebate responsiveness.

Finally, our Canadian results might be a function of survey design effects. However, we find no such effects using independent samples of provincial respondents across the survey’s first four waves (Supplementary Section 20). Accordingly, response consistency in panel surveys is unlikely to account for weak rebate effects47.

Overall, our results speak to growing interest in recycling carbon tax revenues in the form of lump-sum rebates to mitigate persistent public opposition to carbon taxes. We explore existing policies, as implemented, in Canada and Switzerland using a new longitudinal opinion panel as well as two survey experiments. We find only limited evidence that these existing policies have reshaped the politics of carbon pricing to date. Members of the public in both countries remain ill-informed about the rebates they are already receiving and systematically underestimate their size. These low levels of awareness may stem from rebates delivered via a credit against a (tax or insurance) bill rather than a more-visible check in the mail and, in the case of Canada, a highly politicized communication environment. Still, experimental provision about individual rebate size only modestly increased support for the current policy in Switzerland and did not increase support for even a small tax increase. In Canada, information about rebate size did not increase policy support, but instead led Conservative Party respondents to believe the policy imposed net costs on their household.

These findings imply that one-time information does not substantially affect policy support. While results from non-climate domains may not extrapolate to carbon taxation19, previous studies suggest learning over time built public support for congestion taxes48,49,50 and solid-waste charges51. Yet public ignorance of dividends has persisted for more than a decade in Switzerland, and our Canadian panel covered a period in which the carbon tax was highly salient by virtue of the policy’s implementation, court challenges, federal–provincial conflict and partisan debate during a federal election, a most likely case for public learning about the rebate scheme.

Altogether, results from these studies paint a more complex picture of the benefits of lump-sum carbon tax rebates than did previous surveys and laboratory experiments using hypothetical policies. While the climate-dividend policies in Switzerland and Canada diverge from policy ideals, trading off public transparency for administrative efficiency, we note that these are the only two extant examples of carbon tax and dividend globally. Both were implemented in the context of partisan and interest-group debates, including widespread dissemination of selective or misleading information. As always, both policy design and attitudinal change may still occur. The government of Canada has announced that future rebates, which will steadily increase in value, will be delivered to households directly. However, in Switzerland, voters rejected an increase in the country’s carbon tax rate, alongside increased rebates, in June 2021 when faced with intense politicization of policy costs by opponents. The evolution and impact of new rebate designs, increasing tax rates and benefit sizes, and potential shifts in partisan positions remain for future research.

Methods

Our paper draws from four new data sources. First, we report a new survey dataset, the Canadian Climate Opinion Panel (CCOP). Second, we report a survey experiment embedded in the fourth wave of the CCOP. Third, we report a large-n survey of Swiss residents conducted in December 2019. Fourth, we report a survey experiment embedded in this Swiss survey. We discuss each dataset and the methods used to analyse it, in turn.

CCOP

The CCOP was a custom five-wave public opinion panel survey administered online to a sample drawn from the Leger 360 platform. This platform is a web-based pool of over 400,000 Canadians, 60% of which were recruited randomly via random-digit dialling. From this pool, an initial sample of 3,313 panellists was generated for five Canadian provinces: Alberta (n = 663), British Columbia (n = 661), Ontario (n = 660), Québec (n = 661) and Saskatchewan (n = 668). These provinces were selected to ensure representation of provinces subject to the federal carbon tax and dividend as well as provinces exempt from the federal carbon tax because of provincial policies deemed equivalent to the federal carbon price. Respondents were remunerated by Leger at a rate of CDN$1 to CDN$3 per wave depending on survey length.

Panellists were invited to participate in the study and answered the first questionnaire between 21 February and 5 March 2019. During this wave, we obtained 3,313 completes and a combined American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) RR3 response rate of 18%. AAPOR RR3 rates incorporate an estimate of eligibility among respondents of unknown eligibility into the response-rate denominator, offering a conservative response-rate estimate52. Panellists were subsequently recontacted between 10 and 28 April 2019, after the federal carbon tax policy came into effect on 1 April. During this second wave, responses were received from 2,189 returning panellists from Alberta (n = 437), British Columbia (n = 434), Ontario (n = 440), Québec (n = 439) and Saskatchewan (n = 439). An additional 252 respondents (50 from each province except Saskatchewan, where 52 completed) were added to this wave as a check against panel experience, resulting in a total sample of 2,441. The combined AAPOR RR3 response rate for this portion of the fieldwork was 50%. A third invitation went out to panellists between 27 June and 19 July 2019, after the majority (over 96%) had completed their income tax returns and thus would have received their rebate if eligible. In this wave, we secured completes from 1,509 panellists from Alberta (n = 303), British Columbia (n = 301), Ontario (n = 301), Québec (n = 300) and Saskatchewan (n = 304). Another 251 respondents (50 from each province except Quebec, where 51 completed) were added as a check against panel experience, for a total of 1,760 completes. The AAPOR RR3 response rate for this third wave was 49%. We then secured 1,440 completes in the fourth wave following the October 2019 federal election, of which 1,190 were returning panellists. The remaining 250 over sample were equally distributed across the five provinces. The fieldwork for this portion of the study was conducted between 22 November and 16 December 2019. The AAPOR RR3 response rate for this portion of the fieldwork was 56%. Finally, a total of 899 panellists completed a fifth wave of our survey administered between 13 and 28 May 2020. This included 200 from British Columbia, 176 from Alberta, 161 from Saskatchewan, 193 from Ontario and 169 from Québec. The AAPOR RR3 response rate for returning panellists in wave 5 was 76%. Our overall sample was broadly representative of population characteristics of each province, including age, gender, education and income (Supplementary Section 21). The survey received a human subjects review from the Université de Montréal’s Comité d’éthique de la recherche en arts et humanités (certificate CERAH-2019-016-D). All survey respondents provided informed consent before beginning the survey. We find no evidence of systematic attrition of respondents in our later waves on the basis of observed demographic characteristics (Supplementary Section 22).

A concern in any public opinion panel is that respondents are repeatedly exposed to a topic, shaping their beliefs and opinions as a function of panel participation. Panel design effects of this sort can compromise the representativeness of a panel over time. In the context of the present study, panel design effects are of even greater potential concern. Climate dividends, as implemented by the Canadian federal government, are integrated into a complex federal income tax system, which would tend to dampen respondents’ awareness and understanding of the policy. Further, contentious political debates have created a confusing messaging environment for Canadians about the structure, value and presence of carbon pricing policies in various provinces. If panel respondents, by virtue of their participation in our study, became more informed about and engaged with climate dividends, then preference shifts within the panel could be a misleading indicator of the dividend’s effects on the general public’s preferences. To measure potential design effects, we collected a random sample of new respondents during waves 2, 3 and 4 (n = 252 in wave 2, n = 251 in wave 3 and n = 250 in wave 4). These respondents were randomly sampled across the five survey provinces in equal proportion, equivalent to our sampling procedure in the broader panel survey (Supplementary Section 20).

Canada survey experiment

Before deploying wave 4, we estimated the objective rebate received by each survey respondent from Ontario and Saskatchewan, using their province of residence, reported marital status (including common law), number of children residing with them as reported in wave 3 and whether their residence is rural (for example, outside a census metropolitan area (CMA)) and thus eligible for an additional rebate. These factors completely determine dividend levels within the current Canadian policy, which we calculated using Revenue Canada income tax worksheets. Note that dividend levels are not a function of income in Canada. For CMA measurements, we determine the respondent’s place of residence using the Postal Code Conversion File provided by Statistics Canada, which gives us a range of geographic identifying variables (such as residence in a CMA and electoral district) for each of the self-reported postal codes collected in our survey. We summarize the rebate calculation process for 2019 in Supplementary Section 23. As part of an embedded survey experiment in wave 4, we randomly assigned half the respondents to receive a filled-out tax form that showed them their own household rebate amount (Supplementary Section 12).

Details about question wording in our survey instrument are presented in Supplementary Section 24. All respondents were given the option of responding in either English (n = 752) or French (n = 147).

Swiss public opinion survey

We fielded an online survey of 1,050 Swiss residents, quota sampled on age, gender and language, in December 2019. The survey was provided in German and French but not Italian, which is the official language in the canton of Ticino as well as some municipalities in Graubünden. Nevertheless, the survey covers respondents from all Swiss cantons. Overall, the sample quite closely matches the Swiss population; however, as typical for such surveys, the groups of the lower educated (secondary education I) as well as the oldest age groups are somewhat underrepresented (Supplementary Section 26). A copy of the Swiss survey instrument is also provided in Supplementary Section 26. The survey received a human subjects review from the University of California Santa Barbara’s Office of Research Human Subjects Committee (protocol number 21-19-0801). All survey respondents provided informed consent before beginning the survey.

Swiss survey experiment

As part of this December 2019 Swiss survey, half of respondents were randomly assigned to an encouragement treatment, where we asked respondents to pause their survey and retrieve their most recent health insurance form. Respondents were then asked to let us know what the size of their rebate benefit was. Because all Swiss residents receive the same amount, we then displayed a sample document (in their language of survey response) to all respondents in the treated group, whether they reported finding their bill or not (Supplementary Section 15 for example). We then measured respondent support for the existing Swiss policy and their potential support for either a small (from CHF0.25 to CHF0.28 per l heating oil) or large (to CHF0.40 per l heating oil) tax increase (respondents were randomly asked for their preferences on either of these two cost settings). A summary of all variables used as well as descriptive statistics for the Swiss data can be found in Supplementary Section 27.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All supporting data are available through a Harvard Dataverse replication archive at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3WBCH9.

Code availability

All supporting code is available through a Harvard Dataverse replication archive at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3WBCH9.

References

Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends (Climate Leadership Council, 2019).

Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends (European Association of Environment and Resource Economists, 2019).

Harrison, K. A tale of two taxes: the fate of environmental tax reform in Canada. Rev. Policy Res. 29, 383–407 (2012).

Carattini, S., Kallbekken, S. & Orlov, A. How to win public support for a global carbon tax. Nature 565, 289–291 (2019).

Anderson, S., Marinescu, I. & Shor, B. Can Pigou at the polls stop us melting at the poles? National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 26146 (2019).

Thalmann, P. The public acceptance of green taxes: 2 million voters express their opinion. Public Choice 119, 179–217 (2004).

Baranzini, A. & Carattini, S. Effectiveness, earmarking and labeling: testing the acceptability of carbon taxes with survey data. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 19, 197–227 (2017).

Sénit, C.-A. The Politics of Carbon Taxation in France: Preferences, Institutions, and Ideologies (Institut du Développement Durable et des Relations Internationales, 2012).

Mildenberger, M. Carbon Captured: How Labor and Business Control Climate Politics (MIT Press, 2020).

Rhodes, E., Axsen, J. & Jaccard, M. Exploring citizen support for different types of climate policy. Ecol. Econ. 137, 56–69 (2017).

Stadelmann-Steffen, I. & Dermont, C. The unpopularity of incentive-based instruments: what improves the cost–benefit ratio? Public Choice 175, 37–62 (2018).

Levi, S. Why hate carbon taxes? Machine learning evidence on the roles of personal responsibility, trust, revenue recycling, and other factors across 23 European countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 73, 101883 (2021).

Rabe, B. G. Can We Price Carbon? (MIT Press, 2018).

Harrison, K. The comparative politics of carbon taxation. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 6, 507–529 (2010).

Dermont, C. & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. The role of policy and party information in direct-democratic campaigns. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 32, 442–466 (2020).

Lachapelle, E. & Kiss, S. Opposition to carbon pricing and right-wing populism: Ontario’s 2018 general election. Environ. Politics 28, 970–976 (2019).

Beiser-McGrath, L. F. & Bernauer, T. Could revenue recycling make effective carbon taxation politically feasible? Sci. Adv. 5, eaax3323 (2019).

Kirchgässner, G. & Schneider, F. On the political economy of environmental policy. Public Choice 115, 369–396 (2003).

Carattini, S., Carvalho, M. & Fankhauser, S. Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 9, e531 (2018).

Nowlin, M. C., Gupta, K. & Ripberger, J. T. Revenue use and public support for a carbon tax. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 084032 (2020).

Amdur, D., Rabe, B. G. & Borick, C. P. Public views on a carbon tax depend on the proposed use of revenue. Issues Energy Environ. Policy 13, 1–9 (2014).

Dolšak, N., Adolph, C. & Prakash, A. Policy design and public support for carbon tax: evidence from a 2018 US national online survey experiment. Public Adm. 98, 905–921 (2020).

Bachus, K., Van Ootegem, L. & Verhofstadt, E. No taxation without hypothecation: towards an improved understanding of the acceptability of an environmental tax reform. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 21, 321–332 (2019).

Hsu, S.-L., Walters, J. & Purgas, A. Pollution tax heuristics: an empirical study of willingness to pay higher gasoline taxes. Energy Policy 36, 3612–3619 (2008).

Kallbekken, S. & Aasen, M. The demand for earmarking: results from a focus group study. Ecol. Econ. 69, 2183–2190 (2010).

Kallbekken, S. & Sælen, H. Public acceptance for environmental taxes: self-interest, environmental and distributional concerns. Energy Policy 39, 2966–2973 (2011).

Gevrek, Z. E. & Uyduranoglu, A. Public preferences for carbon tax attributes. Ecol. Econ. 118, 186–197 (2015).

Rotaris, L. & Danielis, R. The willingness to pay for a carbon tax in Italy. Transp. Res. D 67, 659–673 (2019).

Kotchen, M., Turk, Z. & Leiserowitz, A. Public willingness to pay for a US carbon tax and preferences for spending the revenue. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094012 (2017).

Bristow, A. L., Wardman, M., Zanni, A. M. & Chintakayala, P. K. Public acceptability of personal carbon trading and carbon tax. Ecol. Econ. 69, 1824–1837 (2010).

Lachapelle, E., Borick, C. P. & Rabe, B. Public attitudes toward climate science and climate policy in federal systems: Canada and the United States compared. Rev. Policy Res. 29, 334 (2012).

Jagers, S. C., Martinsson, J. & Matti, S. The impact of compensatory measures on public support for carbon taxation: an experimental study in Sweden. Clim. Policy 19, 147–160 (2019).

Fairbrother, M. When will people pay to pollute? Environmental taxes, political trust and experimental evidence from Britain. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 661–682 (2017).

Beuermann, C. & Santarius, T. Ecological tax reform in Germany: handling two hot potatoes at the same time. Energy Policy 34, 917–929 (2006).

Kallbekken, S., Kroll, S. & Cherry, T. L. Do you not like Pigou, or do you not understand him? Tax aversion and revenue recycling in the lab. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 62, 53–64 (2011).

Cherry, T. L., García, J. H., Kallbekken, S. & Torvanger, A. The development and deployment of low-carbon energy technologies: the role of economic interests and cultural worldviews on public support. Energy Policy 68, 562–566 (2014).

Klenert, D. et al. Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 669–677 (2018).

Jagers, S., Lachapelle, E., Martinsson, J. & Matti, J. Bridging the ideological gap? How fairness perceptions mediate the effect of revenue recycling on public support for carbon taxes in the United States, Canada and Germany. Rev. Policy Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12439 (2021).

Carattini, S., Baranzini, A., Thalmann, P., Varone, F. & Vöhringer, F. Green taxes in a post-Paris world: are millions of nays inevitable? Environ. Resour. Econ. 68, 97–128 (2017).

Douenne, T. & Fabre, A. Yellow vests, pessimistic beliefs, and carbon tax aversion. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy (in the press). https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20200092&&from=f

Davidovic, D., Harring, N. & Jagers, S. C. The contingent effects of environmental concern and ideology: institutional context and people’s willingness to pay environmental taxes. Environ. Politics 29, 674–696 (2020).

Mettler, S. The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy (Univ. Chicago Press, 2011).

Fiscal and Distributional Analysis of the Federal Carbon Pricing System (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2019).

Quenneville, G. & Hunter, A. Covid-19 in Saskatchewan: province marks ’sad milestone’ of first 2 deaths. CBC News (30 March 2020); https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/coronavirus-saskatchewan-1.5514563

Kumlin, S. & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public: Policy Feedback, Participation, Voting, and Attitudes (Edward Elgar, 2014).

Schwegler, R., Gina, S., Schappi, B. & Iten, R. Klimaschutz und Grüne Wirtschaft - was meint die Bevölkerung? Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung Technical Report (INFRAS, 2015).

Bergmann, M. & Barth, A. What was I thinking? A theoretical framework for analysing panel conditioning in attitudes and (response) behaviour. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 21, 333–345 (2018).

Schuitema, G., Steg, L. & Forward, S. Explaining differences in acceptability before and acceptance after the implementation of a congestion charge in Stockholm. Transp. Res. A 44, 99–109 (2010).

Hensher, D. A. & Li, Z. Referendum voting in road pricing reform: a review of the evidence. Transp. Policy 25, 186–197 (2013).

Andersson, D. & Nässén, J. The Gothenburg congestion charge scheme: a pre–post analysis of commuting behavior and travel satisfaction. J. Transp. Geogr. 52, 82–89 (2016).

Carattini, S., Baranzini, A. & Lalive, R. Is taxing waste a waste of time? Evidence from a Supreme Court decision. Ecol. Econ. 148, 131–151 (2018).

Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys (AAPOR, 2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants (initials of grant principal investigators in parentheses) from a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Granthad (M.M., E.L. and K.H.), theSmart Prosperity Institute at the University of Ottawa (M.M., E.L. and K.H.), the Economics and Environmental Policy Research Network of Canada (M.M., E.L. and K.H.) and the Centre for International Governance Innovation (#5597, K.H.), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#435-2017-1388, E.L.), the Institute for Social, Economic and Behavioral Research at UC Santa Barbara (M.M.) and the Hellman Fellows Fund (M.M.). We thank participants at the UC Santa Barbara Environmental Politics Workshop, Swiss Political Science Association annual meeting, Environmental Politics and Governance conference, L. Fesenfeld, P. Bergquist, C. Fischer, P. Quirk, G. de Roche and C. Hazlett for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., E.L. and K.H. designed, collected and analysed the Canadian data presented here. M.M. and I.S.-S. designed, collected and analysed the Swiss data presented here. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Thomas Bernauer, Nicholas Rivers and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Opposition to carbon pricing by province across waves.

Wave 1 was conducted in February 2019 and wave 5 in April 2020. The dotted line indicates when the federal carbon tax policy came into effect. The solid line indicates the approximate period during which households received their climate rebates. The dashed line indicates the timing of a federal election in which climate policy, including the carbon tax, was highly salient. Respondents in Saskatchewan and Ontario received a federal climate rebate associated with Canada’s 2019 carbon tax. Other respondents were subject to provincial carbon pricing policies that had few, if any rebate, components. Error bars give 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Support for carbon pricing among Liberal and Conservative voters, by rebate vs. non-rebate province.

The dotted line indicates when the policy came into effect. The solid line indicates the approximate period during which households received their climate rebates. The dashed line indicates the timing of a federal election in which climate policy, including the carbon tax, was highly salient. Voters are classified according to their wave 1 (pre-policy implementation) party preferences. Since Alberta only became subject to the federal tax, and thus eligible for the federal dividend, between wave 4 and 5 (and Albertan respondents had not received a rebate as of wave 5), we bundle Albertan data with the non-rebate provinces. Error bars give 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Support for carbon pricing among Liberal and Conservative voters, by cost exposure.

Cost exposure measured by whether respondents report driving alone to work, or whether they report a different means of getting to work (transit, walk, cycle, carpool, work/study from home). Individuals who chose the survey option ‘This question doesn’t apply to me’ when asked how they get to work are excluded from the figure. The dotted line indicates when the policy came into effect. The solid line indicates the approximate period during which households received their climate rebates. The dashed line indicates the timing of a federal election in which climate policy, including the carbon tax, was highly salient. Voters are sorted according to their wave 1 (pre-policy implementation) party preferences and self-reported means of getting to work. Error bars give 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of perceived household rebate sizes for Canadian panel.

Responses from respondents who remained in the panel as of wave 3 and resided in the rebate provinces of Ontario and Saskatchewan. The correct answer for each set of respondents is highlighted in green.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–27.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mildenberger, M., Lachapelle, E., Harrison, K. et al. Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 141–147 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01268-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01268-3

This article is cited by

-

Realizing the full potential of behavioural science for climate change mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

Cost sensitivity, partisan cues, and support for the Green New Deal

Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences (2024)

-

How consumption carbon emission intensity varies across Spanish households

SERIEs (2024)

-

Cross-national analysis of attitudes towards fossil fuel subsidy removal

Nature Climate Change (2023)

-

Light-driven biosynthesis of volatile, unstable and photosensitive chemicals from CO2

Nature Synthesis (2023)