Abstract

Active surveillance trials for low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are in progress in the United States and Europe. In some of these trials, the presence of comedo necrosis in the DCIS has been an exclusion criterion for trial entry. However, the minimum amount of necrosis required by pathologists for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis is not well-defined. We surveyed 35 experienced breast pathologists to assess their diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis. Pink circles representing necrosis ranging in extent from 10 to 80% of the duct diameter were superimposed on eight replicate histologic images of a single duct involved by low nuclear grade, solid pattern DCIS. These images were circulated by e-mail to the participating pathologists who were asked to select the image that represents the minimum amount of necrosis that they require for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis. Among the 35 participants, the minimum extent of the duct diameter required for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis was 10% for 4 pathologists, 20% for 5, 30% for 11, 40% for 7, 50% for 6, 60% for 1 and 70% for 1. There was no single threshold about which more than one-third of the pathologists agreed met the minimal criteria for comedo necrosis. We conclude that even among experienced breast pathologists, the threshold for comedo necrosis is highly variable. Our findings highlight the need for a standardized definition of comedo necrosis as a trial criterion, and more generally where it may be used as a marker of increased risk of recurrence for therapeutic decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the introduction of mammography and population-based screening in the 1980s, the incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has significantly increased [1]. At present, DCIS represents approximately 25% of all breast cancer diagnoses in the United States [2]. Almost all patients who are diagnosed with DCIS undergo complete surgical excision (lumpectomy or mastectomy) with or without radiation and/or endocrine therapy. As such, little is known regarding the natural history of untreated DCIS. Small retrospective studies of untreated DCIS have shown progression to invasive cancer in a variable proportion (20–50%) of cases, low-grade DCIS progressing less often and over a more protracted time course than high-grade DCIS [3,4,5,6]. Given that invasive cancer is not inevitable, overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS is a growing concern[7] and raises the question of whether there is a low-risk subset that can be safely observed after a diagnostic biopsy.

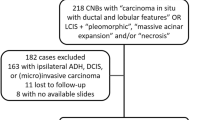

Recently, prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing active surveillance of low-risk DCIS to standard treatment have begun accruing patients: the Surgery Versus Active Monitoring for LOw-RISk DCIS (LORIS) trial [8] in the United Kingdom, the Management of LOw-Risk DCIS (LORD) trial [9] in continental Europe and the Comparison of Operative to Monitoring and Endocrine Therapy for low-risk DCIS (COMET) trial [10] in the United States, among others planned. In addition, a single arm prospective study of low-risk DCIS is under way in Japan (JCOG 1505: LORETTA trial) [11]. Although the patient selection criteria vary to some extent across trials, eligible patients are generally those who have low to intermediate grade DCIS diagnosed via vacuum-assisted core needle biopsy. The presence of comedo necrosis on histopathologic examination has been an exclusion criterion of the LORIS trial, and until very recently, the COMET trial as well.

Our institutions serve as sites of enrollment for the COMET trial. In subspecialty breast pathology practice, we have encountered cases of DCIS with necrosis for which patient eligibility depended upon whether or not the necrosis was deemed sufficient to qualify it as “comedo necrosis”. We have found such cases to be problematic given the lack of a universally accepted definition of comedo necrosis. This experience prompted us to survey other experienced breast pathologists regarding their diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis.

Materials and methods

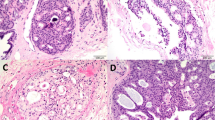

A composite figure containing eight replicate histologic images of a single duct involved by low nuclear grade, solid pattern DCIS was created (Fig. 1). To simulate necrosis, a pink circle of varying diameter was superimposed on the central portion of the duct in each image, selected to represent involvement of 10 to 80% the duct diameter in 10% increments. The images were labeled from #1 to #8 according to increasing duct involvement without specifying the percentage of involvement. This figure was circulated via e-mail to 35 experienced breast pathologists in the United States, representing 20 academic institutions. The pathologists were asked to report “which image represents the minimum amount of necrosis required for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis?” Results were tabulated from e-mailed responses, including the selected image number and any explanatory comments.

Pink circles of varying diameter were superimposed onto eight replicate histologic images of a single duct involved by low nuclear grade, solid pattern DCIS to simulate necrosis representing 10–80% of the duct diameter in 10% increments. The images, labeled only 1–8, were circulated to breast pathologists with the question “which image represents the minimum amount of necrosis required for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis?”

Results

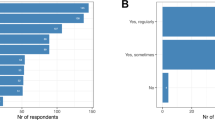

All 35 breast pathologists who were sent the survey responded, representing 20 different institutions. The proportion of duct diameter with necrosis required for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis varied widely among the participating breast pathologists (Fig. 2). The pathologists selected images #1 through #7, which corresponded to 10 to 70% of the duct diameter involved by necrosis. Image #3, representing 30% of the duct diameter, received the greatest number of votes (11 of 35 votes; 31.4%), followed by images #4, representing 40% (7 of 35 votes; 20.0%) and #5, representing 50% (6 of 35 votes; 17.1%). Variation in diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis was observed not only between pathologists at different institutions but also between those at the same institution. For example, pathologists from each of two separate institutions selected images ranging from #3 through #5, whereas pathologists at a third institution selected images ranging from #4 to #7.

Participant comments highlighted the substantial differences in approach to this diagnostic issue and in their working definitions for “comedo necrosis” (see Table 1). Selected strategies included: recognizing comedo necrosis as a type of necrosis irrespective of the extent of the necrotic material, and similarly, diagnosing focal comedo necrosis in the presence of any central necrosis; subjectively selecting an amount of necrosis that appeared to represent more than just focal necrosis; diagnosing comedo necrosis only in the presence of high-grade DCIS; and quantifying necrosis as minimal, moderate or marked instead of using the term “comedo necrosis”.

Discussion

This observational study, which employed a composite image of a single duct profile involved by low-grade DCIS with varying amounts of simulated necrosis, revealed considerable variability in the diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis among experienced breast pathologists. In fact, we observed that there was no single threshold about which more than one-third of the participants agreed met the minimum criteria for a diagnosis of comedo necrosis, and even pathologists working together at the same institution gave differing responses. Our findings highlight the lack of a commonly accepted definition of “comedo necrosis”, an issue of less consequence until the initiation of the recent active surveillance trials for low-risk DCIS in which the presence of comedo necrosis was being used as an exclusion criterion.

Appropriate patient eligibility criteria are critical for identifying a low-risk population of women with DCIS and to the success of active surveillance trials. Comedo necrosis has been incorporated into exclusion criteria due to evidence suggesting that it is a risk factor for contemporaneous invasive cancer and local recurrence. In retrospective studies of DCIS diagnosed on core needle biopsy, comedo necrosis is one of the histologic features that has been associated with upstaging to invasive cancer on surgical excision, although the findings have not been consistent across studies. A meta-analysis of studies published prior to 2011 did not find an increased risk of upstaging of DCIS to invasive cancer in the presence of comedo necrosis in pooled estimates from the 9 studies reporting this variable [12]. Since then, to our knowledge, out of five studies that have investigated the significance of comedo necrosis on CNB [13,14,15,16,17], only two have shown it to be an independent predictor of invasive cancer on excision [13, 14].

Comedo necrosis has also been implicated as a risk factor for local recurrence after breast conserving treatment (BCT) for DCIS. In an analysis of the pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-17 trial [18, 19], which compared lumpectomy alone versus lumpectomy with radiation therapy, moderate / marked comedo necrosis (defined as necrosis present in > 1/3 of ducts involved by DCIS) was an independent predictor of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) at both 5 and 8 years [20, 21]. Furthermore, in the NSABP B-24 trial, which investigated the added benefit of tamoxifen therapy, the degree of necrosis, scored as absent, slight or moderate/marked, was associated with increasing risk [22]. Long-term follow-up revealed that invasive cancer represented approximately half of all IBTRs, with the 15-year risk of this event at 19.4% for excision alone and 8.9% for excision plus radiation [23]. However, the relationship between comedo necrosis and invasive IBTR was not investigated. Of note, in the era of these trials, margin assessment practices did not consistently meet current standards, with involved or uncertain margins present in up to one quarter of patients, potentially impacting risk estimates.

Consistent with the findings in the NSABP trials, the series of studies [24,25,26,27] that lead to the development of the University of Southern California/Van Nuys Prognostic Index (USC/VNPI), a scoring system for DCIS risk stratification, also found that comedo necrosis (originally defined as substantial amounts of necrotic neoplastic cells in the central lumina of any architectural pattern of DCIS) was one of the significant independent predictors for local recurrence. A pathologic classification was developed that divided DCIS into low or intermediate nuclear grade without necrosis (grade 1), low or intermediate nuclear grade with necrosis (grade 2), and high nuclear grade (grade 3) [24]. The overall USC/VNPI score, as determined by addition of scores for the pathologic classification, lesion size, margin status and age [27], was intended to inform management recommendations regarding excision alone, excision plus radiation therapy, or mastectomy. However, this system, which predates modern breast screening, has not been widely adopted due to the lack of validation in clinical trials and reproducibility in clinical practice [28, 29].

A novel pathologic system for grading DCIS was subsequently proposed by Pinder et al. [30] following histopathologic analysis of cases from the UKCCR/ANZ DCIS trial, another BCT trial from the same era as the NSABP trials. In this study, all evaluated grading systems (including the cytonuclear grade and the Van Nuys pathologic classification), as well as the presence of comedo necrosis, showed a significant association with ipsilateral recurrence of DCIS and invasive disease. However, the authors identified a subgroup of high-grade lesions with a particularly poor prognosis, referred to as “pure comedo DCIS” and defined as having (i) high cytonuclear grade, (ii) > 50% solid architecture, and (iii) > 50% of ducts with central confluent type necrosis. A three-tier grading system that divided DCIS into low/intermediate grade, high grade and very high grade (“pure comedo type”) showed a strong relationship with the development of ipsilateral recurrence (rates of 6.1%, 10.9% and 18.2%, respectively), both overall and separately for DCIS and invasive disease. These results suggest that the presence of comedo necrosis may be of greatest clinical significance when extensive and found in the setting of high cytonuclear grade DCIS. Again, similar to the USC/VNPI, this DCIS grading system is based on data from an older cohort and has not been validated.

Recently published data from the Sloane Project [31], an observational population-based study of the features, patterns of care and outcomes of non-invasive neoplasia detected in the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme in the United Kingdom, provided more contemporary evidence regarding the risk associated with comedo necrosis. In this retrospective study of nearly 10,000 women diagnosed with DCIS between 2003 and 2012, high grade and comedo necrosis represented two pathologic factors that were significantly associated with a higher risk of breast events and ipsilateral breast recurrence, although the relationship between these factors and invasive recurrence was not specified. Moreover, in recent meta-analyses of the literature, comedo necrosis has been found to be a predictor of local recurrence [32], but not invasive local recurrence [33].

If comedo necrosis continues to be accepted as an exclusion criterion in DCIS active surveillance trials, then a standardized definition of this histologic finding would be highly preferable to promote consistent risk assessment in trial enrollment and clinical practice. Although not specifically acknowledged in the responses collected in this study, standardized definitions of comedo necrosis have been published. The 1997 Consensus Conference on the Classification of DCIS [34] defined comedo necrosis as “any central zone necrosis within a duct” and comedo as one of the accepted architectural patterns of DCIS. Furthermore, the consensus opinion stated that “the term comedo refers specifically to solid intraepithelial growth within the basement membrane with central (zonal) necrosis. Such lesions are often but not invariably of high nuclear grade.” In contrast, the 2013 College of American Pathologists (CAP) Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) of the Breast [35] classifies necrosis into two subtypes: 1) central (comedo) and 2) focal (punctate). Central necrosis is defined as “an area of expansive necrosis in the central portion of an involved ductal space that is easily detected at low magnification”, whereas focal necrosis consists of “small foci, indistinct at low magnification, or single cell necrosis”. The CAP protocol also states that “although central necrosis is generally associated with high-grade nuclei, it can also occur with DCIS of low or intermediate nuclear grade”. Unfortunately, these proposed definitions differ from one another. In particular, many DCIS lesions that are regarded to have comedo necrosis by the 1997 Consensus Conference Criteria would not be considered to have comedo necrosis by the 2013 CAP criteria, since the 1997 Consensus Conference Criteria are far less restrictive. Subjectivity in what represents “expansive necrosis” in the 2013 CAP criteria further clouds this issue. Finally, no matter the definition applied, it should be noted that assessing the degree of necrosis is not always straightforward, as ducts may be tangentially cut, distorted, or not perfectly round in histologic sections.

The degree of interobserver variability in the assessment of comedo necrosis identified in this study has several implications. First, the results of our study highlight the fact that previously unrecognized or unappreciated levels of variability in the criteria used to define a common histologic feature that has for decades routinely been used in pathology reports may be unmasked when that feature is used as an exclusion criterion in a multi-institutional clinical trial in which many pathologists are involved in determination of trial eligibility. In addition, our results have direct implications for enrollment in trials testing active surveillance for patients with DCIS. A definition of comedo necrosis that is too restrictive may exclude potentially suitable candidates for these trials, whereas a definition that is too liberal may result in the inclusion of patients who may be at an unacceptably high risk for local recurrence or progression to invasive breast cancer. However, it should be noted that the risk of local recurrence or progression to invasive breast cancer in relation to comedo necrosis remains uncertain for the types of DCIS lesions currently encountered in clinical practice, which are most often small, mammographically-detected lesions, unlike those of most older series or clinical trials. Furthermore, the risk attributed to comedo necrosis in some of the prior studies reviewed herein reflects a far more extensive process than that of the minimal threshold required for a diagnosis by consensus definitions and common practice.

As a result of the analysis presented here, the COMET trial protocol was amended to remove comedo necrosis from the exclusion criteria, a change expected to circumvent the confusion and uncertainty about trial eligibility due to diagnostic variability and inconsistent reporting of comedo necrosis. An advantage of granting eligibility to all patients with low to intermediate grade DCIS, aside from the ability to offer conservative management to a greater number of patients, is that the relationship between comedo necrosis and invasive cancer can be further studied in this population.

In summary, we found that the diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis varies substantially among experienced breast pathologists. The results of this study emphasize that before a histologic feature is used as an inclusion or exclusion criterion in a clinical trial, its definition needs to be standardized to ensure its uniform application.

References

Virnig BA, Wang SY, Shamilyan T, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: risk factors and impact of screening. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:113–6.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

Maxwell AJ, Clements K, Hilton B, et al. Risk factors for the development of invasive cancer in unresected ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:429–35.

Rosen PP, Braun DW, Jr., Kinne DE. The clinical significance of pre-invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:919–25.

Collins LC, Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, et al. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1778–84.

Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Simpson JF, et al. Continued observation of the natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ reaffirms proclivity for local recurrence even after more than 30 years of follow-up. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:662–9.

Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, et al. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2205–40.

Francis A, Thomas J, Fallowfield L, et al. Addressing overtreatment of screen detected DCIS; the LORIS trial. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2296–303.

Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L, et al. Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ - The LORD study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1497–510.

Youngwirth LM, Boughey JC, Hwang ES. Surgery versus monitoring and endocrine therapy for low-risk DCIS: The COMET Trial. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2017;102:62–3.

Kanbayashi C, Iwata H. Current approach and future perspective for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:671–7.

Brennan ME, Turner RM, Ciatto S, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ at core-needle biopsy: meta-analysis of underestimation and predictors of invasive breast cancer. Radiology. 2011;260:119–28.

Doria MT, Maesaka JY, Soares de Azevedo Neto R, et al. Development of a model to predict invasiveness in ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosed by percutaneous biopsy-original study and critical evaluation of the literature. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18:e805–12.

Jakub JW, Murphy BL, Gonzalez AB, et al. A validated nomogram to predict upstaging of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2915–24.

Al Nemer AM. Histologic factors predicting invasion in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the preoperative core biopsy. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:429–34.

Hogue JC, Morais L, Provencher L, et al. Characteristics associated with upgrading to invasiveness after surgery of a DCIS diagnosed using percutaneous biopsy. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:1183–91.

Park HS, Park S, Cho J, et al. Risk predictors of underestimation and the need for sentinel node biopsy in patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ by preoperative needle biopsy. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:388–92.

Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, et al. Lumpectomy compared with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1581–6.

Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:441–52.

Fisher ER, Costantino J, Fisher B, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) Protocol B-17. Intraductal carcinoma (ductal carcinoma in situ). The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Collaborating Investigators. Cancer. 1995;75:1310–9.

Fisher ER, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:429–38.

Fisher ER, Land SR, Saad RS, et al. Pathologic variables predictive of breast events in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:86–91.

Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ. Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:478–88.

Silverstein MJ, Poller DN, Waisman JR, et al. Prognostic classification of breast ductal carcinoma-in-situ. Lancet. 1995;345:1154–7.

Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Craig PH, et al. A prognostic index for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 1996;77:2267–74.

Silverstein MJ. The University of Southern California/Van Nuys prognostic index for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg. 2003;186:337–43.

Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD. Treatment selection for patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast using the University of Southern California/Van Nuys (USC/VNPI) prognostic index. Breast J. 2015;21:127–32.

Gilleard O, Goodman A, Cooper M, et al. The significance of the Van Nuys prognostic index in the management of ductal carcinoma in situ. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:61.

MacAusland SG, Hepel JT, Chong FK, et al. An attempt to independently verify the utility of the Van Nuys Prognostic Index for ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 2007;110:2648–53.

Pinder SE, Duggan C, Ellis IO, et al. A new pathological system for grading DCIS with improved prediction of local recurrence: results from the UKCCCR/ANZ DCIS trial. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:94–100.

Thompson AM, Clements K, Cheung S, et al. Management and 5-year outcomes in 9938 women with screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ: the UK Sloane Project. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:210–9.

Wang SY, Shamliyan T, Virnig BA, et al. Tumor characteristics as predictors of local recurrence after treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:1–14.

Zhang X, Dai H, Liu B, et al. Predictors for local invasive recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2016;25:19–28.

Consensus conference on the classification of ductal carcinoma in situ. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1221–5.

Lester SC, Connolly JL, Amin MB. College of American Pathologists protocol for the reporting of ductal carcinoma in situ. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:13–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the breast pathologists who participated in our survey in addition to authors B.H. and S.S., without whom this study would not have been possible.Constance Albarracin, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.Kimberly Allison, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA. Sunil Badve, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN. Gabrielle Baker, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. Ira Bleiweiss, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Jane Brock, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. Edi Brogi, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. Laura Collins, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. James Connolly, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. Yunn-Yi Chen, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA. David Dabbs, Magee-Womens Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA. Susan Feinberg, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY.Hannah Gilmore, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH. Thomas Gudewicz, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Xufei Hong, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, Boston, MA. Timothy Jacobs, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Shabnam Jaffer, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY. Kristen Jensen, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA. Erinn Downs Kelly, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.Gregor Krings, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA. Melinda Lerwill, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.Susan Lester, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. Jonathan Marotti, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH. Melissa Murray, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. Juan Palazzo, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA. Liza Quintana, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. Mara Rendi, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Jordi Rowe, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Dennis Sgroi, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Sandra Shin, Albany Medical College, Albany, NY. Donald Weaver, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT. Hannah Wen, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. Tad Wieczorek, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, Boston, MA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrison, B.T., Hwang, E.S., Partridge, A.H. et al. Variability in diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis among breast pathologists: implications for patient eligibility for active surveillance trials of ductal carcinoma in situ. Mod Pathol 32, 1257–1262 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0262-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0262-4

This article is cited by

-

Is conservative management of ductal carcinoma in situ risky?

npj Breast Cancer (2022)

-

Is loss of p53 a driver of ductal carcinoma in situ progression?

British Journal of Cancer (2022)

-

Low-risk DCIS. What is it? Observe or excise?

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Learning to distinguish progressive and non-progressive ductal carcinoma in situ

Nature Reviews Cancer (2022)

-

Multi-modal imaging of high-risk ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast using C2Am: a targeted cell death imaging agent

Breast Cancer Research (2021)